Therapeutic Inductions

Before we get going on these book notes. I am not a therapist, and I’m not certified (yet) for changework… I’m still debating finishing my MMHA up. I’ve been working quite a bit with Hypnosis Without Trance, and that got the ball rolling in reframing my perspective on inductions. If there’s a few highlights form this book, it’d be…

- Look at inductions as the experience your subject has, not as a tool to hypnotize them.

- Build your inductions with intent.

- Consider your inductions as an extension of your pre-talk, and your goals within them.

- Be intentional with your inductions - while modern hypnosis argues that you don’t need and induction for phenomenological control, you can absolutely therapeutic (and recreational) work inside of induction in a hypnotic ritual.

1 - Introduction

Section titled “1 - Introduction”The goal of this book is to take you from induction basics (structure, effectiveness, individual compatibility) all the way to having an understanding of how to modify them to be therapeutic.

2 - A Brief History of Hypnosis

Section titled “2 - A Brief History of Hypnosis”- Franz Mesmer - 1734-1815. Initially - Mesmer applied magnets to patients, causing them to convulse. Later, he began to believe that he was the cause of these effects through animal magnetism - a rationalist idea of the era. His popularity crested, but then eventually waned after moving to France, his theories on animal magnetism being investigated and met with skepticism.

- Marquis de Puysegur - 1751-1825. A follow of Mesmer. He began attempts to induce a state called ‘artificial somnambulism’ instead of the abreaction-like convulsive responses Mesmer would create - using techniques that look more like modern hypnosis… (🦈 How the F do you say their name anyway?)

- James Braid - 1795-1860. Dismissed Mesmerism as unscientific, modified the techniques of mesmerists and coined the term hypnosis. They later coined the term ‘monoideism,’ but it didn’t quite stick.

- James Esdaile - 1808-1859. A Scottish surgeon that boasted about performing “300 major [operations], including 19 amputations, all painlessly.” (Notes from Clinical Hypnosis and Self Regulation suggest that these may have slightly less painful than claimed. I’d be willing to go out on a limb and say this is correct.)

- Ambroise-Auguste Liebault - 1823-1904. Remixed Mesmerism and Braid’s ideas, and founded the Nancy School of hypnotism with Bernheim. They tried to shift away from the ritual components and move towards suggestion.

- Jean-Martin Charcot - 1825-1893. Sometimes called the father of modern neurology - they leaned into hypnosis as a psychological state. His ‘Paris School’ eventually lost to the ideas of the Nancy School.

- Hippolyte Bernheim 1840-1919. A follower of Liebault. Gave credibility to the psychological model of hypnotism.

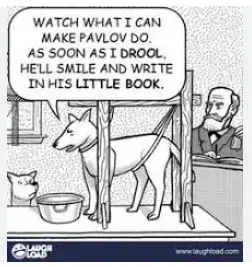

- Ivan Pavlov 1849-1936. The drooling dog guy. Created a physiological model of hypnosis based on these reflexes.

- Sigmund Freud -1856-1939. Initially took some of Bernheim’s writings and translated them into French and German. He initially in one of this books considered regression therapy through hypnosis, but later abandoned it for his own ‘psychoanalytic’ method. The poor dude had a rough ride out.

- Emile Coue - 1857-1926. Briefly assisted in Liebeault’s clinic before developing his own theory and giving seminars on his self-help method.

- Pierre Janet 1859-1947. Coined the word subconscious. Hey - you can’t have subconscious without sub. Emphasized psychological dissociation.

- Clark Hull 1884-1952. President of the APA - did the first well-regarded scientific research on hypnosis.

- Milton Erickson 1901-1980. Influenced and improved the use of indirect suggestion. Didn’t do much for the actual science. Ernest Rossi may disagree but meh.

- Ernest Hilgard 1904-2001. Psychologist and professor at Stanford. Developed the neo-dissociation theory of hypnosis. Later, suggested the ‘amnesic barrier.’

- Theodore Sarbin - 1911-2005. One of the earliest researchers to suggest cognitive-behavioral theories of hypnosis. Argued that hypnosis could be more easily understood through theories of social behavior than state theory.

- Andre Weitzenhoffer - 1921-2004. Considered the true father of modern hypnotherapy. Critic of Ericksonian and cognitive-behavioral approaches.

- Martin T. Orne - 1927-2000. Researched social ‘demand characteristics,’ drew upon elements of state and non-state theories, and warned about memory distortion with hypnosis. Responsible for the concept of ‘trance logic.’

- Theodore X. Barber - 1927-2005. Developed the cognitive-behavioral theory of hypnosis, and produced a large body of evidence that hypnosis was not a special state.

- Nicholas P. Spanos - 1942-1994. Researcher in non-state hypnosis, worked on the CSTP.

- Irving Kirsch - 1943-present. Suggests hypnosis and placebo both share response expectancy effects. His (and Lynn’s) response set theory, he not only rejects state theory but also compliance-based expectation. Hypnotic context intensifies the the effects of suggestion, but is not the sole mechanism.

Other models:

- Hypnosis as Relaxation - theorizes ‘anesis’ (hypnosis as relaxation) reduces inhibition, improves attitudes, improves ego functioning, intensifies dissociation, and enhances role-playing.

- Integrative models - I’ll put this less politely than Graham, but integrative models seek to calm the academic bloodbath between state and non-state theories. Graham also leaves a tip that psycho-social theories are the ones to keep an eye on.

- Cold Control Theory - I’ve written a lot about this on the site, but the TLDR is “executive control without conscious awareness.” Graham also highlights this as one to watch.

- Hypnosis as REM Activation - A brand new theory! Theorizes hypnosis is an artificial activation of the REM state. Human Givens is researching this. Cool!

- Automatic Imagination - A mixture of cold control and Kirsch’s ideas. Interestingly developed by Anthony Jacquin and Kev Sheldrake.

I agree with Graham (and Yapko) in that any single of model of hypnosis is likely inadequate to explain it’s effects. Continuing in agreement, hypnosis may be more than one single thing.

TLDR: be flexible and aware as you work.

3 - An Experiential Model

Section titled “3 - An Experiential Model”Highlighting that the previous chapter demonstrates why a strict definition of hypnosis is both unhelpful and unlikely, Graham drops his own definition:

As I present it, hypnosis is not something you do to another person, or a thing that they go into. Hypnosis is an experience you share with someone.

…

An imagination-fuelled, creatively engaged, shift in a person’s perception of the world & their relationship to it.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 29). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

Graham does the following to explain hypnosis:

- Walking through the experience of a horror movie, there your hairs will raise or you’ll respond automatically.

- You’re very aware that it’s not real. But a part of you is going “What if?”

- (You can use this to subtly look for responses, right here, while you’re describing a film or asking them to remember something!)

- Graham gives an experiential explanation of hypnosis by simply using magnetic hands.

- However, in a fun twist, they invite their head to drop forward as their hands drop into their lap.

- They say that’s what hypnosis is like - when you imagine and engage with something so effectively it becomes part of your reality.

- After that - they reinforce (genuinely and honestly) that whatever they felt was normal.

- They go back to the movie (if that seemed to resonate with their client)…

- They highlight the absurdity of being emotionally moved by a millionaire actor pretending to die.

- They highlight that this works by accepting the reality of the movie for the next 2 hours.

- They also highlight that it’s hard to be absorbed in a crap movie.

Hypnosis can feel…

- Relaxed

- Trancey (entrancement is an emotion, as mentioned by Binaural Histolog)

- Dissociated - a split experience

- Focused

- Involuntary

Clients will less often ask “what is hypnosis,” and are more curious about “what will I experience.” Your goal isn’t to drown your client in nuance, but to build a path towards doing hypnosis with the client, supported by your explanation.

Sometimes, covertly, they’ll use the Fractionation Conversation to get a demonstration in. While in a recreational setting - this is a bit sketch, doing this in a therapeutic setting makes perfect sense. They wrap it up by saying the experience is the easiest way to explain it.

They highlight the following 4 bits as important to the client to simplify understanding:

- Eye closure

- Controlled breathing

- A mental image to re-experience

- Each breath letting their body and mind relax

In conclusion - when someone asks “what is hypnosis,” if it’s coming from a client (or a friend,) they’re probably more interested in the experience than a scientific model.

4 - What Does an Induction Do?

Section titled “4 - What Does an Induction Do?”Hey - if you’ve got a study buddy, Graham says now’s the time to give them a pop quiz and ask them what an induction actually does.

Here’s some ideas…

- They increase suggestibility. Graham notes that research does not heavily support this, but I’m going to throw my own thoughts in here. He cites correctly that Irving Kirsch (a socio-cognitive theorist) concludes that the increase is minimal when it’s there. But - Irving Kirsch still uses inductions. Graham is also unlikely to be playing with the untherapeutic sledgehammers we casually wield in the recreational community.

- To Get Someone Into Hypnosis! The author says this explanation is useless - as we can’t clearly define what hypnosis is in the first place, and state-theory is shaky at best.

- Inductions Build Expectancy. I’m personally in this camp - but Graham reframes this. Inductions can go two ways - reinforcing the client’s expectations, or disappointing them. They also say that inductions are unlikely to create expectancy out of thin air. They cite (I think) this journal. (Also, from the book club, there’s other talks about the CSTP not replicating.)

- An induction technique is a vehicle for your confidence, your persona, your intent to hypnotize. Anthony Jacquin said this. Graham’s on board with this - you become the reason they shift their perception of reality. I like this more in theory than in practice for reasons I wrote about in my notes on Reality is Plastic.

- Teaching compliance. They highlight that while compliance sets are a thing, it’s unlikely that an induction itself will build compliance if it was not there before. (Again, Graham knows his stuff, but I think there can be some stark differences between therapeutic and recreational settings.)

They highlight that whenever we’re doing street hypnosis, or James Tripp’s Hypnosis Without Trance method, we’re doing hypnosis without an induction.

Why bother with inductions then?

Section titled “Why bother with inductions then?”Graham highlights that, whatever you do to start to shift and reshape someone’s experience, is when your induction begins. They really want to drive this point in.

The moment you begin to engage another person’s reality, to make it be what you want it to be, you have induced – or you have begun to induce – hypnosis. So, let’s give that moment some credit. Let’s not rush it, dismiss it, or discredit it.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 50). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

From an experiential standpoint, these things are components of an induction:

- Building Rapport and Expectations

- Assigning roles

- Frame-setting (boundaries and intent)

- Framed as a Learning Experience. (Or - what can we teach our client during an induction.)

In this frame, where inductions are defined as the starting point for hypnosis, they’re unavoidable. (They do have an amusing take on it. 😆)

…the early stages of any conversation sets the character of the interaction… to put it crudely, induction-less hypnosis may be the equivalent of trying to take someone to bed without even buying them a drink.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 52). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

5 - The Anatomy of Inductions

Section titled “5 - The Anatomy of Inductions”Man. I love what Graham writes in here. I’ll still summarize the useful bits, but I’ll leave his intro as a treat for the reader if you end up buying this book. I’m enjoying the ride quite a lot so far.

I’ll continue writing from Graham’s point of view. Again - I don’t agree with anything, but his perspective is excellent, and frankly, the dude knows more than I do.

Anyway.

Look for the following elements as good ingredients in any induction:

- Gain Consent / Get Contract

- Build Expectancy

- Absorb Awareness / Attention

- Engage Imagination

- Arouse Feelings / Awareness

Consent and Contract

Section titled “Consent and Contract”Rapport is not just being liked by your client - but being on the same page. They start by asking the client what they want, and then tell the client what they want to get back as well. You’ll have to finesse this socially, but Graham’s looking for…

- Honest answers

- Don’t share anything they want to keep to themselves

- Don’t force, fake, or fight anything

- Maybe mention a technique or two you’d like to try, or a conversation you’d like to have.

This creates the aforementioned contract when both agree.

Build Expectancy

Section titled “Build Expectancy”Expectancy can come from the client’s context - movies or experiences in the past, or the pre-talk and an immediate experience that you can control. Key moments in an induction (the quickness of an Elman induction, or an arm-pull being surprising) highlight something significant is happening. They also hint that your client’s absorption and awareness are a key part to how they attribute the expectancy you’re trying to build.

Absorb Attention / Awareness

Section titled “Absorb Attention / Awareness”Ideally, your client’s attention and awareness should be pointed at either what you’re saying or their experience.

Engage the Imagination

Section titled “Engage the Imagination”In a therapeutic setting, inspiring someone’s imagination is one of the best tools you have. This can apply in…

- A phobia living in imagination. Show them how strong and flexible their imagination is, then take a crack at adjusting it.

- Simply having them imagine relaxing somewhere.

- Provide metaphors or stories.

Graham notes that people that say they ‘cannot imagine’ and ‘cannot relax’ sometimes turn out to be excellent at it. It’s worth double checking to make sure that they know that visualize and imagine are two different things.

…if I say something like “picture yourself at the top of a staircase,” it can mean a whole range of things from see, imagine, realise, pretend, or find yourself. Part of that is about active versus passive imagination (because poor visualisers often over-estimate what good visualises see and how they see it), and part of it is providing a broader meaning to the word imagine than merely visualising something.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 59). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

Arouse Emotions / Feelings

Section titled “Arouse Emotions / Feelings”Emotions and feelings will allow someone to engage with their imagination, reinforcing your reframe attempt. The induction itself should be meaningful.

Troubleshooting

Section titled “Troubleshooting”You don’t need all 5 of these aforementioned elements for an effective session, but they suggest it can be used as a troubleshooting guide. (Or heck, even as food for thought to figure out what went well.)

6 - Therapeutic Inductions

Section titled “6 - Therapeutic Inductions”A few thoughts from the author on how to do more with your induction. His approach differs in that an induction is not just something you do to get someone into ‘hypnosis,’ but to actually help out with something. This is therapeutic frame setting - EG, if someone has stress issues, kick it off by relaxing them with a PMR.

Perhaps of relevance to the recreational crew - to throw into your bag of thoughts of ‘therapy’ vs ‘therapeutic.’:

I should clarify here that when I speak of something being ‘therapeutic,’ I am not only thinking of clinical hypnosis. All hypnosis can be therapeutic. Even sticking someone’s hand to their pint of Beer can teach them about the power of their mind and how to use that power to undergo shifts in their perception and experience of reality.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (pp. 64-65). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

They also present inductions as a ‘reframe ritual,’ which I quite like. This can be a ‘flick of the switch’ to reframe something during the ritual, to make a major change, after being shown you may have more resources available to you than first thought.

‘Psychotherapy is at its best when it is weird.’

- Jeffery Zeig

Also - an induction could be seen as an opportunity for the client to learn what they need to do to move forward - or at least learning what they need. This can be spontaneous like a quick switch, or progressive like change over time.

7 - Categories of Induction

Section titled “7 - Categories of Induction”Graham suggests you can combine two or more of “building blocks” to do your own therapeutic induction. The chapter includes transcripts of various inductions which I won’t reproduce here. If you feel like these would help, buy the book!

Categories:

- Eye Fixation

- It doesn’t have to be a real thing to fixate on, it can be imagined.

- Progressive Relaxation

- Also includes guided imagery.

- Mental Confusion

- Experientially, we suggest we go inside to investigate the confusion, or escape the confusion by “letting go.”

- Confusion inductions are not necessarily ideal for ‘analytical clients.’ The are good for clients that have trouble shutting off some part of their mind.

- Confusion techniques are more about utilization than a battle of wills.

- Physical Phenomena

- Has components of relaxation, confusion, and surprise… may not be it’s own category.

- Has a weird experience that’s difficult to make sense of. Examples being…

- Being rocked rhythmically

- A loss of balance (PULL!)

- Phenomena that build imagination and expectancy

- My favorite quote from here is “Let’s thank Lisa and her arm for coming-up, shall we?” (from the induction transcript)

- Surprise

- Rapid inductions, usually using a sudden shock or setting something off balance right when you give a suggestion

- Revivification and Re-Inductions

- Bringing back previous experiences of ‘relaxation or absorption.’

- Includes Graham’s very own leisure induction.

- Sometimes, even the process of entering hypnosis can be a learning experience, for the subject.

A quick tip on pressing for more…

S: “It’s difficult to put into words…”

H: “It is, isn’t it?”

S: “Yeah.”

H: “But I know you’re gonna try…”

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 83). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

Building Blocks

Section titled “Building Blocks”While these can be seen as building blocks - the point here isn’t for you to categorize things, but to find new ways to remix tools and inductions. You might even have something with a ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ building block.

8 - Selecting Your Induction

Section titled “8 - Selecting Your Induction”🎶You can be a lover or a fighter, whatever your desire… (sorry)

Picking an induction should include consideration of…

- What your client’s goals are

- What your goals are

- Your own approach - are you direct / indirect / authoritarian / permissive

Be mindful in your approach. If you see someone as being easily pushed around, an authoritarian approach may effective, but not the most therapeutic. In my recreational applications, subverting these expectations has been effective. In a case where someone expects to be roughed up by their hypnotist, I took a gentle and permissive approach, and they found it absolutely intoxicating.

Remain flexible and if it turns out that you’ve chosen the wrong induction or approach for the person in front of you, learn from it and move on. After all, that’s exactly what you would want your client to do.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (pp. 89-90). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

- Passive, Relaxed, Easy-Going People

- Almost anything will work. Lean maternal. They might be bummed out if they’re used to meditating or relaxation, and you just gave them the same experience.

- Powerful / Successful People

- Either take charge or give permission - avoiding the middle ground. Take into consideration your own style.

- Analytical

- It’s not a bad thing they’re always thinking - they’re already absorbed. If you go authoritarian, go fast to avoid analysis. If you go slow, use permissive language or confusion. Teach them fractionation. Use convincers.

- Subordinates (EG - guards, police)

- They’re comfortable with and good at following instructions - you can be authoritarian. Go for something that leans quick. But, everyone’s an individual - your mutual goals are more important than effectiveness.

- Metaphysical / Spiritual

- They have great imaginations - use that! A good excuse to use My Friend John. “Subconscious” suggestions are a hit as well.

9 - A Solution-Focused Approach

Section titled “9 - A Solution-Focused Approach”So - ask…

- To reach their goal, what does your client need? Either skills or resources.

- To use that, what frame of mind do they need?

- What sort of experience do they need for 1 and 2?

Try thinking about where you’re going, rather than what’s in the way. So for someone terrified of Nickelback songs, what state of mind would you like them to be in while listening? (Bemusement? Indifference? Mild annoyance?)

Overall, consider the tools they already have at their disposal, and see if you can apply them. They may have already solved a similar problem elsewhere, or have the tools they need to solve the current problem.

Tools for Figuring Out Solutions

Section titled “Tools for Figuring Out Solutions”- Ask “If not that, then what?”

- EG - C: “I don’t want to scream and cry when Nickelback comes on to the radio.” H: “If not, then what?” C: “I really just want to zone out, not care, and hopefully not hear it.”

- “How do you cope?” (It can be insightful.)

- Without seeming dismissive, ask about when things are going well (or their current coping tools are working.)

- What do you look like in a parallel universe? Or - walk them through a thought exercise where they can see themselves in another setting not bothered by whatever the thing is. Walk them through conversationally. This almost makes me think of future pacing. Graham gives an example where they have a client talk how they’d like to be without a fear of bridges, and they collect the nominalization “You’re nonchalant.”

- They also note that sometimes they don’t like the version of themselves where they no longer have the problem! If they like the sympathy they get, you might talk with them about that instead.

- “Give me a clue.” A technique where they ask their client to imagine a little movie clip from the future, it’s not the whole story of how things have improved, but a quick snip.

- “What was the key?” Uh 😅 - ask them to do your job for them.

- Something like…

- Usually this isn’t a massive change or revelation.

- If I said I had this problem, and you only had 5 or 10 minutes to sus it out, what would you say? Just to get things moving.

- What might be the key difference?

- They might not know! Try…

- But what if you did know?

- Humor me.

- What might part of it be?

- If you had to guess?

- Give them as much time as they need.

- Something like…

- What would make the problem impossible? (EG - what frame of mind would they be unaffected in.)

- Suggest you’re sharing a visual hallucination/imagination of two monitors - and you’re plugged into it. You can’t see what your client is doing on their monitor, and a role model on another. Walk through the differences, say you can only see what ‘their brain’ is doing, but not what they’re doing. Keep it sciency (and don’t insult them.) Maybe your client will forget which brain they’re describing and they’ll help themselves out. =)

10 - Therapising Your Induction

Section titled “10 - Therapising Your Induction”This chapter focuses on the 3 questions from the previous chapter…

- What resources/tools do they have that they can use.

- What frame of mind do they need?

- How do we use 1 and 2 in our induction?

A few examples, from transcripts of his live training event.

A dude anxious about getting on a train:

- They find the problem and have them describe it.

- It’s in front of a crowd, they highlight that they’re not alone in feeling this way, since a lot of people raised their hands when asked if they feel anxious about jumping on to some jank public transport.

- In highlighting this, they dissociate by asking “what do you think people that didn’t raise their hands are thinking when they’re getting onto the train?”

- The participant said they were focused on their destinations ideally - so… Graham asked if that’s how he would want to feel?

- The participant said they’d like to feel serene - like Bruce Lee.

- Graham dug in a bit more, asking when they last felt that.

- They used an Erickson style ambiguous touch to start to move them into a state of focus, bringing them to that feeling. He asked them how easily Buddhist monks (brought up earlier) step onto a train, but suggested that right now, they could just as easily dissociate. They cracked an in-joke about being in the Bruce Lee zone, but helped them absorb themselves in that feeling, suggesting they may picture themselves getting on that train, and finding how easily they can come back to this state.

So…

- They remembered being serene taking walks.

- To get there, they could dissociate and be calm.

- And they got there through ambiguous touch rapidly, but were shown they could easily get back to this state.

A participant that has issues with their mother in law.

- The participant highlighted the tension they felt. They would like it to be ‘easy’ - like the occasional argument.

- Digging in, they said that they’d like to have the courage to say something.

- Graham asked when they were happy with themselves last - they said in a bubble bath, literally saying it was like the perfect PMR.

- They use the frame of the Elman induction, fractionating them into the feeling of that bubble bath.

- Graham had them relax away the numbers.

- They slipped in a metaphor about lions needing to eat first before feeding their cubs - indirectly suggesting they need to monitor their own needs.

- Then brought them to a chalkboard and forget the letters of tension, forgetting it for a moment.

- They wanted to feel relaxed, without tension. I don’t see how it fits into this 1-2-3 framework, but Graham picked up on that she needed to be able to recognize the tension in her body and her own stress, and separate that from the moment.

- They needed to be in a brave frame of mind to do this.

- In erasing the tension, they were able to temporarily forget about it and be in the moment.

Unorganized Notes

Section titled “Unorganized Notes”- You can reframe phenomena to make it more comfortable. “You CAN’T move your arm” can be changed to “your arm will be so relaxed it just won’t move, that’s it.”

11 - Creating Therapeutic Inductions

Section titled “11 - Creating Therapeutic Inductions”It feels tactless to reproduce the checklist for creating therapeutic inductions from the book here, so - here’s an overview.

- Know what approach to take

- Answer “The 3 Questions”

- Pick a Theme (EG - induction delivery device - like eye fixation)

- Include the Elements of Hypnosis (EG consent, expectancy)

(Or… 3 Questions, 4 Approaches, 5 Elements, 6 Themes as a memory aid.)

When you’re doing the thing - don’t focus on the charcuterie board of things to do to them therapeutically, focus on THEM.

Here’s come thoughts on the ‘building blocks’ (themes) for inductions.

- Eye Fixation and Absorption - you can use this on it’s own, or combine it with confusion to ‘splash them in the face with water’ then redirect their focus elsewhere.

- Progressive Relaxation - For stress. (In agreement with Graham, maybe don’t tell them they should relax, that’s almost insulting.) Relaxation can also be useful when the ‘investment in the issue is part of the problem.’

- Mental Confusion - when their own mind is getting in the way - not an ‘analytical person,’ but more like someone whose trapped in rumination. Useful for redirecting conscious thought.

- Physical Phenomena - anywhere where physicality (performance) is an issue - this can show them they’ve underestimated their capabilities. Or - this can be useful where automatic responses need to be examined.

- Surprise - everything with confusion - plus the ability to make rapid changes.

- Revivification - a shortcut to re-entering an experience. It’s salt. Use it everywhere.

The 3-4-5-6 is something you think about as you are working - things to look for, as things fall into place.

A previous student told me that it sounded as if the way I intuit these items is to treat each client as a cutie. I was somewhat unsure what she meant until she gave me the acronym AQTE – Approaches, Questions, Themes, Elements.

Old, Graham. Therapeutic Inductions: Rethinking Hypnosis from the Very Beginning (p. 141). Plastic Spoon. Kindle Edition.

12 - Conclusion

Section titled “12 - Conclusion”Graham implores you to…

- Think of inductions as tools for making change or giving suggestions, not just for improving expectation or suggestibility.

- Consider hypnosis from the client’s experiential viewpoint more than a theoretical standpoint. Or, as Graham puts it - “not as something you do to someone, but as an experience they go through.”

Graham plugs their website - H2Di - how to do inductions. I can personally recommend it as well, noting that they also do live trainings.

Personally, I can also recommend many of Graham’s books. Their Induction Masterclass series is solid - my particular favorites are Mastering the Leisure Induction, The Elman Induction, or Hypnosis with the Hard to Hypnotise. They’re my favorite author on hypnosis.