Hypnosis and Conscious States

Heck. I’m in over my head reading literal neuroscience… Yes - I’m aware of the inherent irony of that statement.

So, please take my digested notes with the same caution you’d use listening to your stoned roommate talk about set theory.

1 - Introduction

Section titled “1 - Introduction”Graham A Jamieson

The introduction offers - you guessed it, an introduction and overview of the chapters.

Section 1, comprised of chapters 2-5, will cover ‘functional brain networks.’

Kicking it of, chapter 2 will examine hypnotic analgesia. The experience of pain is generated by a “functionally heterogeneous network” spanning cortical and subcortical regions. The way the regions interact is important, not just the regions themselves.

Chapter 3 covers, disappointingly, that current approaches centered around the Stroop effect, EEG and magnetoencephalography (MEG) techniques are unable to differentiate “conflict detection and cognitive control.” There’s a bit of context in here that it’s an “encouraging example of researchers working together” despite “conflicting empirical findings and theoretical perspectives.” Interestingly - they found that high responders in hypnosis experienced more Stroop interference until they were given suggestions on how to work with the interference. Extending that, they proposed that the very mechanism impaired by hypnosis, making them experience more Stroop interference, may be the very thing that helps the hypnotized person follow suggestions.

More simply - usually, without suggestion, they’d be able to avoid Stroop interference to a certain degree. This ability to avoid Stroop interference was weakened after inducing hypnosis. Then after giving suggestions on how to get around Stroop interference, they performed well. They could be using the same tool to enter a hypnotic state as they would (without suggestion) to reduce Stroop interference.

Nuance man. I’m not sure on my interpretation on this one, but I think I’m right! 😅

Chapter 4 discusses neurophysiological differences between hypnotic analgesia and old-fashioned distraction.

Chapter 5 explores the relations between gamma oscillations (whatever those are) and perceptual illusions in the hypnotic experience.

Moving on to Section 2, in chapters 6-7, they will touch on (vaguely) dissociation and the nature of the experience. Chapter 6 gives some perspective on Hilgard’s hidden observer. Chapter 7 proposes that there may be a disruption in the supervisory attentional system (SAS) and an automatic contention scheduling system. 🤷 They follow this up by saying hypnosis cannot be explained by just contention scheduling or a shutdown or disruption between brain regions.

Section 3, covering chapters 8-11, will touch on our favorite controversy - state theory! Both sides have declared the existence and absence of observable state, highlighting it’s need for further investigation. Chapter 8 provides some ideas on how to do neurophysiological research without reinventing the wheel. In a surprising turn, Steven Jay Lynn and Irving Kirsch (along with others) makes a cameo in Chapter 9 - providing a cognitive neuroscience compatible approach to studying the response expectancy model. Chapter 10 provides a “Phenomenology of Consciousness Inventory (PCI)” tool that (I think) correlates well with PET studies, trying to identify related subsystems, without the need for a PET. Chapter 11 surveys how we could use fancy new EEG advances to try to find state, not suggesting whether or not it exists.

Section 4, covering chapters 12-16 covers the “psychobiology of trance experience,” leaving the door wide open to both interpretation and golden nuggets of insight.

They also make the argument that if we can explain a lot of this stuff with cognitive behavior, we should focus on the weird phenomena that only happens in hypnosis. Chapter 12 talks about the possible evolutionary, neurobiological, and developmental history of hypnotic response. Chapter 13 covers the affective and motivational components of creating hypnotic state, not just the propositional (cognitive) content. It’ll attempt to place these other two ingredients in a neuroscientific context. Chapter 14 examines absorption from a neuroscience lens.

Now here’s something cool, Chapter 15 takes a look at the correlation between time shortening and hypnotic susceptibility. This might sound like small beans, but - consider that much of hypnosis could have straightforward socio-cognitive explanations. Therefore - shouldn’t we be focusing on the neat stuff that’s slipped through the cracks? I’m excited to read this one.

And then we wander over to Chapter 16 - cold control theory. It’s a conceptual framework as an extension of Higher Order Thought (HOT) theory, which attempts to provide explanations of why some suggestions are more difficult, and why hypnotic suggestions feel automatic. I still don’t feel cold control explains hypnotic phenomena as a whole, but it explains a hell of a lot.

2 - Hypnotic regulation of consciousness and the pain neuromatrix

Section titled “2 - Hypnotic regulation of consciousness and the pain neuromatrix”Melanie Boly, Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville, Brent A Vogt, Pierre Maquet, and Steven Laureys

Hypnosis has three main components (According to Spiegel, 1991):

- Absorption - becoming fully involved in a perceptual or ideation experience

- Dissociation - mental separation of components that would normally be processed together (dreamlike state of simultaneous actor/observer in memory, or involuntariness in motor function)

- Suggestibility - Responding automatically to suggestion, suspension of critical judgement - possibly a byproduct of Absorption

Brain stuff:

- Activation in the midcingulate cortex (MCC) is related to generating mental imagery, as is done in hypnosis

- Compared to the alert state, there is decreased activity in the medial parietal cortex (precuneus.) There are theories suggesting this region is used for monitoring the world around us. There is the relationship between a misbehaving precuneus and comas, vegetative states, REM, and amnesia.

Hypnotic Analgesia:

Section titled “Hypnotic Analgesia:”- They’ve split pain up into two components - unpleasantness (affective component) and perceived intensity (sensory component.)

- In a study - hypnosis reduced both components by 50% compared to the resting state. For people starting out distracted as part of a study - they were still able to knock down both components by 40%.

- The MCC appears to modulate both of these components.

- The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and MCC are “functionally very heterogeneous regions thought to regulate the interaction between cognition, sensory perception and motor control in relation to changes in attentional, motivational, and emotional states.”

- The MCC is hangin’ out at just the right spot in the brain to get sensory noxious input and the affective components of pain encoded in the ACC.

- The MCC modulates a network of cortical and subcortical regions that deal with noxious stimuli, as well as the pre-supplementary motor area (SMA)

- The MCC also does stuff with motor function - working with the SMA.

- The insula takes a position between the lateral (sensory-discriminative) and medial (affective-emotional) pain systems.

FMRI and Hypnosis

Section titled “FMRI and Hypnosis”- In an FMRI, they saw differences in sensation between hypnotic state and control conditions for painful laser zaps, but didn’t see much difference between the two when the laser wasn’t cranked up enough to be painful.

- “In the hypnotic state… high intensity stimuli only activated primary somatosensory cortex, confirming the dramatic differences in brain processing of… [pain, as compared to without hypnotic induction.]“

3 - Cognitive control processes and hypnosis

Section titled “3 - Cognitive control processes and hypnosis”Tobias Egner and Amir Raz

Cognitive neuroscience is interested in the subjective shifts in automaticity, as it’s an example of top-down mechanisms affecting bottom-up processes. However, it’s unlikely that all hypnotic phenomena can be described as an extreme but normal top-down cognitive control process.

For this paper - they’re going to look at two views of hypnosis. One being that those that are highly hypnotizable are able to strongly focus their attention, and the second being that once these people that are able to strongly focus their attention are hypnotized, their ability to control their attention is impaired.

So… What’s cognitive control?

Section titled “So… What’s cognitive control?”For this journal - they’re defining cognitive control as whatever processes handle “flexible management of processing resources for optimal task performance.”

To try to measure this, they’ll mostly be using examples that include congruent, neutral, or incongruent examples and try to have the test subjects respond to target and distracter dimensions. Or TLDR - things like the Stroop effect. They openly admit that these tests cannot disambiguate what specifically is contributing to this cognitive control.

In usual Stroop tests, they can demonstrate where cognitive control is upregulated or downregulated. EG - if you give some a lot of responses in a row that are congruent (blue text, written with the word blue,) control is usually downregulated. Upregulation occurs when there’s more conflict, in anticipation of future conflicts. So, with their theory, they can measure selective attention by gauging how much the study participant is adapting.

Brain stuff:

- The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC), and parietal cortex are more active when processing incongruent stimuli

- The dACC appears to modulate with the degree of conflict, rather than on the conflict itself. EG - it’s more activated by a “surprise” in overall low-conflict tests, than a constant barrage of incongruent tests.

- The lPFC is opposite - activating in conditions where there’s high control and low conflict. “[the] lPFC is particularly activated after trials on which the dACC exhibited high activation due to conflict, and the degree of such lPFC recruitment predicts the level of conflict reduction on the subsequent trial…”

- Hell I wish they said this first: The dACC detects conflict, and the lPFC makes strategic adjustments in the amount of control. Personal note: real brain science is way beyond my understanding, but it’d be interesting if the dACC and lPFC show anything interesting during a ‘yes’ set.

Hypnosis in relationship to control

Section titled “Hypnosis in relationship to control”In a tiny study, people were given a post-hypnotic suggestion to manipulate their arousal (focus.) The highs had more Stroop interference in low arousal, and higher interference all around than lows or mid responders. However, this doesn’t apply to folks in hypnosis - they were just following a post-hypnotic suggestion.

In hypnosis in the Stroop test, highs responded with slower reaction times (duh, they’re zonked,) and then improved with task specific suggestions. People less susceptible did not show this behavior. (The lows ended up spontaneously coming up with their own strategies for dealing with the Stroop test.)

Interestingly, in the hypnotic condition for all levels of responsiveness, reaction time was slowed from baseline, and did not interact with susceptibility.

With cool brain science, looking at event-related potentials (ERP), another study hypothesized that “hypnosis in highly hypnotizable subjects involves the inhibition of frontal executive functions… hypnosis seems to attenuate consequent processes of contextual updating of the error occurrence…” The highs in hypnosis were less aware that they’d made an error, measured by ERPs.

(The authors did note that the Stroop test can be affected by many processes - so don’t draw any huge conclusions from so this research regarding cognitive control.)

Okay so - on to the cool stuff. This feels like a long-shot, but one study guessed that high responders might just be blurring their vision. So they pharmacologically induced cycloplegia - or from my best guess, knocked out their eye muscles for a bit with some eye drops. Everyone performed better, but there was clear boost specifically for the high responders and low responders instructed to ‘look away.’ The authors suggested this might indicate “a genuine suppression of lexical word processing.”

Conclusions (and Guesses)

Section titled “Conclusions (and Guesses)”- Highs may be better at implementing suggestions than lows.

- Possibly, highs in hypnosis may be impaired from implementing their own strategies, but this same mechanism may allow them to freely implement a suggested strategy.

- According to the research reviewed here, hypnotic response lines up with the ‘impaired attention’ perspective. (And since it can almost feel like this paper is ragging on highs, I’ll add that they said that “with task-specific strategic suggestions, highly susceptible individuals can perform exceptionally well.”)

- “The costs and benefits of hypnotic performance could be related to a breakdown in communication between a medial frontal performance-monitoring system and a lateral frontal cognitive control system.”

4 - Cortical mechanisms of hypnotic pain control

Section titled “4 - Cortical mechanisms of hypnotic pain control”Wolfgang HR Miltner and Thomas Weiss

Noiception (sensing pain) requires translating noxious stimuli into code that can be understood by neurons, as well as transforming information from peripheral/visceral receptors to the central nervous system.

…pain should be defined as a private experience whose individual qualia depends on each individual’s capacity of cognition and emotion, its previous experience, the socio-cultural context and the individual behavioral capacities of pain control…

Neuroscientific accounts of hypnotic analgesia say it’s probably…

- A distraction

- A phenomenon where processing is disrupted or disorganized because of a “dissociation of neural communication between brain areas.”

Hypnotic analgesia and distraction may share the same brain mechanisms. But - that might be misleading - despite the fact that in some studies, hypnotic analgesia and distraction share similarly reported subjective pain intensity.

High-responders showed amplified event-related potentials (ERP) as compared to the control condition, clearly demonstrating the mechanism is not the same as distraction. It’s worth noting that only highs (for this specific test) had favorable responses to hypnotic pain reduction - lows actually felt worse than even the control condition. (Personal note: this is not a conclusive statement that lows cannot be helped with hypnosis, but it is good to keep in mind that this isn’t a bandage appropriate for everyone.)

In another comparison, distraction was almost as good as hypnosis in highs.

The breakdown in the communication between neural modules

Section titled “The breakdown in the communication between neural modules”This is where I need an actual neuroscientist to chime in.

Gamma band oscillations - which are associated with information encoding, are less in sync across brain regions during hypnotic anesthesia. This is hypothesized to reflect a functional breakdown in the ability for the brain to organize emotional and behavioral responses to pain.

Gruzelier claims hypnosis includes some degree of frontal inhibition, and some recent studies support this assertion. “Prefrontal gamma EEG activity located in the (anterior cingulate cortex) ACC predicted the intensity of subjects’ pain ratings in the control condition.” This correlation was only observed in highs.

5 - Phase-ordered gamma oscillations and the modulation of hypnotic experience

Section titled “5 - Phase-ordered gamma oscillations and the modulation of hypnotic experience”Vilfredo De Pascalis

I never thought having a background in audio would help me understand neuroscience or hypnosis, but here we are. This is also where I’d love someone that understands neuroscience and EEGs to offer a layman’s overview - since I’m trying to make something approachable that I don’t fully understand. I’ve taken quite a few liberties in trying to summarize this journal.

So - here’s a quickie rundown of EEGs, and what the article will cover:

- You know when you see someone hooked up to a bunch of electrodes like a hair net, and another machine recording a slew of charts? That’s an EEG reading. It’s reading vague electrical activity in the brain.

- So, gamma oscillations are oscillations in the 40hz range. If you’re in to audio, think of a sine wave. If this was music, this would be in the range that would rattle your junk - very deep, hardly audible. Put more simply - it’s a signal that repeats 40 times a second.

- Now that we’ve got that out of the way - we can look at these waveforms across the brain. They do some spectrum analysis to figure out the phase and correlation of activity - or more simply - does this shit line up. They talk about synchrony - this is just phase correlation. Put more simply - how delayed are the 40ish hz waveforms from each-other. Do the humps line up? They’re in phase. Slightly delayed? Out of phase. Upside down, or 180 degrees out of phase? Inverse phase - or just delayed a half cycle.

The TLDR is that there’s evidence there’s an EEG observable process for inhibiting pain. It’s assumed to be “global,” meaning there’s not just one way to do this (EG - it might just be a byproduct of whatever’s going on after an induction.)

There’s some research that indicates synchronous gamma-range oscillations in the brain have something to do with both sensory awareness and encoding information. It could also be a measure of “functional connectivity.” In neuroscience - there are two schools of thought on encoding and representation - either a ‘pool’ of cells encode information, or there’s a ‘distributed system’ for encoding. They’re guessing that by seeing similar signals at distal parts of the brain, and seeing how in sync they are, you can tell if brain areas are working together - and there’s some evidence to show this.

Misc notes:

- Different types of meditation practice show that there are gamma activity changes in “self-induced alterations in conscious states.” For example, some long-term Buddhist practitioners showed high-synchrony high-amplitude gamma oscillations during meditation.

- A 40hz signal could be a marker of focused arousal. This could be where the idea of hypnosis being a state of focused attention comes from.

- Highs show a lower baseline of gamma activity. However, highs also have a stronger ability to recall emotional events. Highs showed more activity in both hemispheres when recalling positive emotional events. On negative emotional events, they had less activity in the left and more activity in the right. After induction, highs showed significantly lower gamma intensity than others.

- Over the course of an induction, highs started with an increase of gamma density over both hemispheres, and by the end of the induction, a decrease in the left hemisphere, and an increase in the right. Lows showed a decrease in both. In highs, at the beginning of the induction, there was an increase of beta2 (20-30 Hz) amplitude on the left hemisphere, and then at the end when activity decreased, both sides showed the same decrease, making the hemispheres similar. The beta2 band is “intrinsically linked in the ‘encoding’ of active perceptual representations into longer term memory structures.”

- Gamma band dynamics may play a critical role in negative hallucination. There is pain-linked gamma activity in the ACC. This was not altered in lows to hypnosis, but completely disappeared in highs when given hypnotic analgesia. Highs in hypnosis had significant reductions in “phase-ordered gamma activity” during hypnotic analgesia - similar to those suggestions of blocking a visual stimulus. This area is still being researched.

- Highs are more susceptible to perceptual illusions. “Perceptual illusions related to hypnotizability include autokinetic movement, the Ponzo illusion, and the Necker Cube and Schroeder Staircase illusions.”

6 - Hypnosis and the unity of Consciousness

Section titled “6 - Hypnosis and the unity of Consciousness”Tim Bayne

Tim Bayne, a philosopher of mind, argues that there’s no breakdown in “the unity of consciousness.” They also argue that the most likely way to explain the hidden observer paradigm is with “switching” the contents of consciousness, rather than simultaneous and disunified streams of consciousness. This is mostly in regards to state-based takes on hypnosis, usually attributed to Hilgard’s view that the unity of consciousness is an illusion.

But hey - you’re here for fun stuff too - so… Here’s a neat induction framework describing using the idea of the hidden observer:

When I place my hand on your shoulder, I shall be able to talk to a hidden part of you that knows things are going on in your body, things that are unknown to the part of you which I am now talking. The part of you to which I am now talking will not know what you are telling me or even that you are talking.

(Knox et al. 1974, p. 842)

Two models of the hidden observer

Section titled “Two models of the hidden observer”In the two streams model - the global unity is lost between streams. The subject has a ‘central’ stream and a ‘hidden observer’ stream.

A bottom-up report of pain would be from the conscious experience of the actual pain from a cold water experience. A top -down interpretation would be conscious awareness of the pain - but the conscious thought would come from the subject’s imagination, not from the stimulus. Both bottom-up and top-down theorists see these observations from different sources, they both agree that these are conscious states.

An alternative to this is the zombie model. With this - both the perception and report would be unconscious. This doesn’t suggest that the subject is unconscious, just that the states that generate these responses are unconscious.

Hilgard seemed to side with the zombie model.

He writes: ’… the “hidden observer” is a metaphor for something occurring at an intellectual level but not available to the consciousness of the hypnotized person’

The Zombie Model

Section titled “The Zombie Model”

(FWIW, since this guy’s a philosopher, he’s talking about philosophical zombies. They can do normal person stuff, but they lack conscious awareness.)

Just because a subject ‘reports’ a hidden observer, does not mean there’s actually hidden observer. The observation of a hidden observer is usually a byproduct of a suggestion. If the hidden observer is correct, verbal reports of the content from the hidden observer should be globally unavailable as well. Global availability is clearly unavailable during dreams (where weird unexplainable events happen,) and you are indeed conscious while you a dreaming, so global availability is not indicative of consciousness. The other idea is that the unconscious thoughts are only unavailable to something like working memory, but that would mean they’re available to many other systems.

(I’m not sure I follow all this logic here. I probably botched it - but the zombie model was almost certainly presented just to highlight it’s implausibility.)

The two-streams model

Section titled “The two-streams model”Cool - so if the zombie model’s wrong, the states that generate these reports need to be conscious. This two streams model would involve a radical departure from normal, well-studied consciousness. There are studies of patients with part of their corpus callosum cut out, and uh - hypnotic subjects don’t operate like these quite literally split-brained people.

Parallel thoughts can happen in the same stream of consciousness - EG - when you’re listening to what someone’s saying, and you’re planning what you’ll respond with.

One of the arguments for the two-streams model is that there’s no need to find logic between the two streams. EG - believing in a hallucination, while at the same time knowing it’s just a hypnotic hallucination. However - this isn’t proof of two streams - the Muller-Lyer illusion allows you to perceptually experience two lines as different lengths, even though they’re the same length.

Kirsch and Lynn proposed something for the “neo-dissociationist” view. (The source article is called “Social-cognitive alternatives to dissociation theories of hypnotic involuntariness,” so it’s likely they were being generous.)

Responses to suggestion are produced by a division of the executive ego into two parts, separated by an amnesiac barrier. On one side of the barrier is a small hidden part of consciousness that initiates suggested actions and perceives the self and the external world accurately. On the other side is the hypnotized part of the consciousness that experiences suggested actions as involuntary and is not aware of blocked memories or perceptions to which only the hidden part has access.

(Kirsch and Lynn 1998, p. 67)

The ending argument against this is - when prompted, the subject can report their hidden observer experiences… that kind of defeats the idea that it’s hidden.

The switch model

Section titled “The switch model”An explanation of the hidden observer should show why hidden observer probes differ from normal probes. Hilgard suggested the hidden observer would provide a bottom-up account of the stimulation (not top-down, which would be a true experience,) which was conscious. Asking about the hidden observer would only make it’s account reportable, but not change whether or not it was conscious (since the hidden observer was already conscious before.) (Huh? I don’t think I get it. But I’m trudging on…)

The subjects’ verbal reports were retrospective, while their foot-pedal reports were concurrent with the stimulus. The pedal-pressure reports of hypnotized highly hypnotizable individuals indicated increasing levels of pain over the duration of the task, while no equivalent increase of pain over time was indicated via retrospective verbal report. Miller and bowers themselves suggest that changes in the focus of the subjects’ attention might account for the discrepancies between their verbal reports and their foot-pedal reports.

Tim Bayne argues that there is no observable breakdown in consciousness during hypnosis.

7 - Dissociated control as a paradigm for cognitive neuroscience research and theorizing in hypnosis

Section titled “7 - Dissociated control as a paradigm for cognitive neuroscience research and theorizing in hypnosis”Graham A Jamieson and Erik Woody

These notes are based around likely an older version of this linked document. My print version is probably a bit out of date and I don’t want to re-read this. This was not written with home-gamers like me in mind. Here’s my understanding of their point of view.

Hilgard’s amnesiac barrier theory of hypnosis tried to use a rare phenomena (spontaneous amnesia) to explain most of hypnosis. Bowers rebranded the dissociation in Hilgard’s theory to mean that the dissociation has more to do with control subsystems that can be directly and automatically activated, rather than depending on some higher level of executive control.

The supervisory attentional system (SAS) and contention scheduling system (CS) in reference to dissociated control theory (DCT) supposes there’s a breakdown in functional connectivity between anterior and posterior cortical regions (those associated with the SAS and CS.)

New research says that while some parts of the SAS are impaired, hypnosis isn’t a simple shutdown in frontal activity or connectivity. Therefore, if any of this is correct, it’s more likely that Hilgard’s original idea that just aspects of experience and control are dissociated, not a full breakdown.

7.2 Dissociated control theory

Section titled “7.2 Dissociated control theory”The CS system picks schemata to activate based on sensory input and other active schemata. The SAS kicks on to lend a hand when there’s a need to modify these mostly reflexive behaviors. The SAS is for goals, intentions, and monitoring CS. It does not directly implement actions - it’s more of a negotiation manager. According to DCT, there’s a dissociation between the CS and SAS, loosely similar to “some respects… of frontal lesions.”

7.3 Testing dissociated control

Section titled “7.3 Testing dissociated control”While some (Stroop effect related) studies support disruptions in specific SAS activity, there’s no imaginary ninja providing a careless frontal lobotomy.

7.4 Conceptual problems for dissociated control

Section titled “7.4 Conceptual problems for dissociated control”The suggestion “forget the number four” uh - unfortunately, inherently includes the concept of the number four. Dienes and Perner think the SAS is just inhibiting the usual response.

The DCT doesn’t really explain where the new negative or positive content comes from - even if the response is the hypnotee bluescreening. This highlights how the DCT is incomplete.

7.5 Lessons from the neuroscience of voluntary motor control

Section titled “7.5 Lessons from the neuroscience of voluntary motor control”The cerebellum may take part in comparing sensory feedback with intention. When these match up (in a normal motor movement,) the cerebellum inhibits some representations in the parietal cortex.

In an arm levitation study (with separate voluntary, hypnotic, and machine-assisted motion), they saw neurological behavior congruent with this theory. They propose they saw the mismatch of intention awareness when they saw increased cerebellar activation in hypnotic highs. (And thus, the mismatch explains how the movement registered as involuntary.)

7.6 The role of the anterior cortex in cognitive control

Section titled “7.6 The role of the anterior cortex in cognitive control”The SAS model indicates cognitive control is done with top-down biasing - and a study guessed this happens in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and prefrontal cortex (PFC.) The ACC handles monitoring and control adjustments, and the PFC handles “task representations.”

7.7 DCT and the cognitive neuroscience of cognitive control

Section titled “7.7 DCT and the cognitive neuroscience of cognitive control”(I’m a bit rough on my understanding of this so uh - if you really need to understand what’s going on… Maybe ask a Real Neuroscientist. Some chunks in here do start to look like cold control, covered in Ch 16 in this book.)

There are (at least) two levels/orders of SAS that we can look at. The highest level handles “non-routine cognitive and motor responses.” The second order modulates implementation. This second layer, handled in the ACC, looks for conflicts in the representations in the PFC. This second layer tries to signal and make changes to the PFC.

Since it’s the PFC handling the error-checking, the ‘involuntary’ nature of hypnosis might have more to do with an impairment of the secondary layer, more than the first layer. In line with DCT, there may be a disruption between the ACC and PFC.

7.8 Signaling the adjustment of cognitive control

Section titled “7.8 Signaling the adjustment of cognitive control”(I didn’t find anything noteworthy in here.)

7.9 Differing roles of rostral versus dorsal ACC in hypnotic experience

Section titled “7.9 Differing roles of rostral versus dorsal ACC in hypnotic experience”Lining up with hypnosis, some PET studies of hypnotic hallucinations and real stimuli show more rostral (auditory) and caudal/dorsal (pain) ACC activity, as compared to imagined stimuli.

7.10 Further development of DCT

Section titled “7.10 Further development of DCT”They’ve provided two new modified DCT proposals:

- “Top-down biasing” in hypnosis cannot be done with just CS, but also requires interaction with the SAS. Conflict monitoring in the ACC may be unable to adjust the “active control of PFC representations.”

- It’s a guess, but they may be able to figure out how “control breaks down” in the ACC’s conflict monitoring functions, and perhaps explain the ACC’s function in more detail.

8 - New paradigms of hypnosis research

Section titled “8 - New paradigms of hypnosis research”Graham A Jamieson and Harutomo Hasegawa

Hypnotized persons are required to cooperate but not comply, in the literal sense with the hypnotist’s suggestions. This instills a particular motivation to adopt a mental framework consistent with the suggestions of the hypnotist (Shor 1962). This important motivational component of hypnotic response has traditionally been termed rapport. A theory of hypnosis is therefore a theory of phenomena in which the interplay of social, affective and cognitive elements is inextricably bound. At the same time, it is a theory of phenomena with essential expressions in phenomenological, behavioural and physiological domains.

8.2 The need for convergent inquiry

Section titled “8.2 The need for convergent inquiry”Thus the methodological paradigms developed by researchers from radically differing theoretical perspectives may serve to act as a hermetic seal preventing data from within alternative paradigms.

8.3 Levels of explanation

Section titled “8.3 Levels of explanation”Wagstaff himself believes that the pursuit of a unifying theory of hypnosis is misguided. As he states, ‘If we have not been able to find the explanation for hypnotic phenomena, it is not because we lack the technology; it is because there is no single explanation for all hypnotic phenomena’.

8.4 Domains of explanation

Section titled “8.4 Domains of explanation”Me: Because subjective experiences (psychological phenomena, including hypnosis) are inextricable from physiological phenomena, we should see those experiences as an expression of the underlying reality, not as a layer of explanation. So, here’s the new stuff we can do now that we have systems-level neuroscience… Describing this in 3 domains…

Already studied:

| Experiential | Informational | Physical |

|---|---|---|

| Contains: “Holy shit my arm moved! Wowee!” | Contains: Amnesiac barrier, SAS influence | Contains: Observable society and individuals, Cells, Atoms |

| Hypnotic experiences. | Information processing related to hypnosis. | Behaviors and neurophysiology related to hypnosis. |

| New stuff we can actually study: |

| Experiential & Informational | Physical & Informational | Experiential & Informational |

|---|---|---|

| How’s experience relate to information processing? | How’s information processing work with neurophysiology? | How’s experience work with observable behavior and neurophysiology? |

8.5 Cognitive neuroscience and integrated explanation

Section titled “8.5 Cognitive neuroscience and integrated explanation”Now that we have the tools to verify our guesses on how hypnosis and the brain works - we need to develop and test new theories. Just because we can correlate physiological measures to hypnosis, doesn’t mean they’re definitive proof of any underlying mechanism. Or… put brutally…

The logic of such an inference is analogous to:

- ‘Rover’ has 4 legs

- A chair has 4 legs

- Therefore, ‘Rover’ is a chair.

Most correlates are so ambiguous you could tailor the explanation to fit what you believe.

8.6 Hypnosis and altered states of consciousness

Section titled “8.6 Hypnosis and altered states of consciousness”

Let’s get into it - from a few summarized perspectives, unceremoniously misrepresented in my voice similar to what it’d be like after two drinks.

- Kihlstrom: Screw physiological markers - we can see spontaneous amnesia, patients undergo painless surgery, people have negative hallucinations. There are obvious alterations in consciousness, and it doesn’t matter if they happen after an induction.

- Kirsch: Does anything unique actually happen after an induction? If it does, is the phenomena dependent on it?

- Tart: Dude - like… so… If we have an altered state of consciousness, it needs to be altered. But we can define altered to be whatever we want, and that’s kind of the point.

- Biological naturalism: With hypnotic phenomena and response, we should…

-

- See physiological representation of shit happening… and…

-

- We need to see isomorphism, not just a correlation, with phenomena and physiology.

-

Wait wait I was actually interested!...

TLDR: an altered state is not well defined.)

According to Tart…

- State of consciousness is “whatever your brain is up to at the moment”

- a d-SoC (discrete state of consciousness) is a “unique, dynamic pattern or configuration of psychological structures, an active system of psychological subsystems” - staying within a d-SoC isn’t affected by like - small cognitive changes (like changing from reading a book to drinking tea) - it ‘retains it’s identity and functions’ (works the same way)

- a discrete altered state of consciousness (d-ASC) needs to be different from baseline and some restructuring of consciousness. “Altered is intended as a purely descriptive term, carrying no values.”

So, they’re looking for changes in structure/behavior that overlap and extend beyond normal consciousness. So in investigating an altered state of consciousness, they’d look for…

- a change in physiological dynamics

- isomorphism (not just correlation) with the phenomena and observable physiological stuff

Jamieson and Hasegawa contend that an an altered state of consciousness would also be expressed in an altered state of brain networks (change in behavior.) If they can find that, then they can find what could be neural correlates of a state.

Or some quotes external that nail the vibe and say the quiet part out loud…

Would you still enjoy Christmas if there was no Santa Claus? Can we get on with it?

-Vreahli, Fishmatist

I always think of it as “yes, it’s an altered state of consciousness cuz if it isn’t, I’m going to change the definition so it is” :P

…

Why aim for the goal when you can just move the goal posts?

-Internet Tiger

8.7 Altered states of consciousness and altered states of brain networks

Section titled “8.7 Altered states of consciousness and altered states of brain networks”In their framework…

- An altered state of consciousness ASC needs to be expressed in a discrete altered state of brain networks (ASB)

- Fitting with their definition, this happens in REM sleep: “sleep should be regarded as a reorganization of neuronal activity rather than a cessation of activity.”

- This also in an absence seizure: cellular and molecular changes imitate those of REM sleep.

8.8 Testing for altered states of brain consciousness

Section titled “8.8 Testing for altered states of brain consciousness”Oh man… a few quotes - but probably nothing helpful unless you’re a researcher.

- ”… an ASB corresponds to a discrete change in the dynamics which regulate the spatial and temporal flux of physiological brain states.”

- “If there is no change in the organizational dynamics (as distinct from highly specific brain events) that map onto the changes in the organizational framework of conscious experience (as distinct from the specific elements within conscious experience) associated with highly susceptible individuals in hypnotic contexts, then there is no state of hypnosis.”

They end the chapter inviting the reader (uh, sorry guys,) as well as state and non-state researchers to join them in this change of paradigm.

9 - Hypnosis and neuroscience: implications for the altered state debate

Section titled “9 - Hypnosis and neuroscience: implications for the altered state debate”Steven Jay Lynn, Irving Kirsch, Josh Knox, Oliver Fassler, and Scott O Lilienfeld

All right - we’re back to talking about state theory. While I’m tired of listening to these folks throw hands like it’s the YouTube comments section, these arguments are helpful for interpreting academic literature and conclusions in general.

The authors divide these theories roughly into…

- State theorists - there’s an observable state of consciousness that causes or is required for hypnotic effects, and the observed neurological behavior correlates to something special

- Non-state theorists - there’s observable changes in consciousness, but they don’t denote a special or unique state of hypnosis, even if cool mind-bending things are happening

- “Weak” altered state theories - we see changes in consciousness, but they’re not the cause of hypnotic response.

Trance state theorists have had a few guesses (or what they feel are proven theories or models):

- “De Benedittis and Sironi (1988) stated, ‘the trance state is associated with the hippocampal activity, concomitant with a partial amydaloid (sic) complex functional inhibition.”

- Gruzelier said: ‘We can now acknowledge that hypnosis is indeed a “state” and redirect energies earlier spent on the “state-non state debate”.

- Maquet said they found the ‘functional neuroanatomy of hypnotic state’.

- Woody and Szechtman said they can clearly observe the brain operates differently in hypnosis

In this sometimes uncharitable back-and-forth argument, Gruzelier said: ‘Kirsch and Lynn (2998) and Wagstaff (1998) claim that no marker of a hypnotic state has been discovered after decades of investigation, and that the search for one should be discontinued. A neurobiological explanation does not exist. Neurobiologists may rightly wonder how such an unworldly view exists’

The (non-state) authors defend themselves stating that they never said there’s no marker, the search should be discontinued, or that there’s no neurobiological explanation. They did say most researchers find the state theory to have “outlived it’s usefulness,” markers may eventually be found, and it’s important to find the physiological substrates of hypnosis.

That was a lot - have a fish gif.

9.1 The effects of suggestions

Section titled “9.1 The effects of suggestions”The non-state view acknowledges there’s genuine alterations in consciousness in hypnosis. However, when Peter Bloom proclaimed “We now have the proof: Words change physiology!”, the non-state theorists also backed up that this was never the debate. Different hypnotic experiences probably activate different brain regions, and they may not have much in common. Moreover, different people probably produce their responses through different strategies.

Brain activity was measured with PET in two studies. The first study’s suggestions modulated unpleasantness, while the second one changed the sensation, where they saw different responses in the brain.

Participants’ responses correlated with physiological responses

- In Spiegel’s 2003 review, they saw ERP modulation in the sensory association cortex with respect to…

-

- Visual stimuli

-

- Olfactory stimuli

-

- somatosensory perceptual stimuli

-

- suggestions for hypnotic numbness

-

The cool bit - hypnotic suggestions do cool things in the brain that “closely resemble those produced by actual perceptual experiences.” But a ‘state’ of hypnosis isn’t required to observe this.

Using PET, Kosslyn found that there’s changes in blood flow with hypnotic color observation suggestions that look a lot like when people actually see a specific color. Kosslyn concluded that they found evidence of neurological correlates, and that they weren’t just “adopting a role.” The authors explain that yeah, there are neurological correlates, and non-state theorists aren’t saying people are just taking a role, but this also isn’t proof of a hypnotic state. They asked the subjects to “remember and visualize” in comparison to asking them to “perceive” the color, changing neurological behavior.

9.2 Individual differences in hypnotic suggestibility

Section titled “9.2 Individual differences in hypnotic suggestibility”While non-state theorists attribute response initially to socio-cognitive variables (beliefs, expectancies, cognitive strategies, imagination,) state theorists assign responsiveness to the ability or predisposition to enter state. Both sides can benefit from finding how response differs physiologically in regards to baseline suggestibility.

Non-state suggests baseline suggestibility could be attributed to…

- anxiety (either over response or lack thereof)

- predisposition for role involvement, including fantasy proneness

- something not exactly response expectancy, but related to it

There are plenty of correlations to hypnotic response - but it’s clear not all of them can be causal.

- social background, “socio-economic status”

- physiological - basal cortisol levels, immune function

- self-report measures of affect and personality

- shyness and social anxiety

- memory for sad narratives

You wouldn’t say “oh, you’re good at hypnosis because you’re middle class.” It’s just as shortsighted to say “oh, we see strong response in your ACC and your ERPs behave hypnotically - you’ll rock this state thing.”

An example state argument…

“highly hypnotizable individuals have more physiological flexibility involving an active inhibitory process of supervisory executive control by the anterior frontal cortex”

On sort of a tangent - it’s important who academic literature measures in their studies. Many studies compare highs to lows to try to get a read, but they’re probably shooting themselves in the foot. They’re sometimes…

- Artificially inflating variance and effect sizes

- Assuming response linearity where mids may respond like lows or highs

- Preventing accurate interpretations - do mids have trouble because they’re having the same problems as lows, or do mids respond like highs

Or - if you want the author’s direct spicy take (edited slightly for politeness):

We expect that the ‘extreme group’ strategy that is typically used in the literature may be as limited in the domain of hypnosis as attempts to understand gifted children by comparing them with profoundly [mentally impaired] children, or by comparing schizophrenic patients with the best adjusted, most highly functioning individuals in the population. To understand the neurophysiology of hypnosis, it is important to assess subjects with a medium level of suggestibility, as well as those with high and low suggestibility.

We might be seeing behavior in lows related how they’re dealing with the suggestion. EG - maybe they’re frustrated with their response (or lack thereof.) It also may be that the “low” responders are weird, rather than the high ones.

9.3 Hypnosis as a State

Section titled “9.3 Hypnosis as a State”Irresponsibly using neuroscience can create the concept of state based just on interpretation.

For example, people have seen the ACC involved in (and thus attribute it to) comparing internal states to external events, checking how well a response worked, overcoming habits, or even how you see someone you love in comparison to your friends. Your ACC is clearly not just the “friend zone comparison tool.”

As Bentall (2000) noted, without good psychology, neuroimaging research amounts to little more than a particularly ‘dazzling reincarnation of phrenology’

9.3.1 Gruzelier’s neurophysiological theory

Section titled “9.3.1 Gruzelier’s neurophysiological theory”Gruzelier theorizes that enacting hypnosis…

- Engages “left anterior selective attention processes” (focusing)

- Which follows to “selective frontal lobe and limbic inhibre brain, associated with relaxed imagery

While there is evidence of this, some studies show increased frontal lobe activity. Wagstaff also pointed out that frontal lobe inhibition can occur with just following instructions.

9.3.2 Kallio and Revonsuo’s hypothesis

Section titled “9.3.2 Kallio and Revonsuo’s hypothesis”Kallio and Revonuso looked at primarily “highs” that can enter into hypnosis just by telling them to go into a trance. They also suggested we could see hypnosis in these people with direct suggestions to hallucinate (where hypnosis would be the cause of hallucination.) You could think of this as the “slipping into hypnosis” hypothesis. This is so loose that it doesn’t really define a clear altered state of consciousness or behavior, and so specific to people that respond to people direct suggestion incredibly well.

9.4 Methodological Limitations

Section titled “9.4 Methodological Limitations”Thoughts on methodological limitations:

- Having a control group without hypnosis causes obvious problems - esipecially when searching for an altered state of consciousness.

- You’d have to produce the same hypnotic phenomrena in both hypnotized and non-hypnotized individuals. Then, you could search for neural correlates or changes in behavior.

- Some studies used role-players to compare - but there’s nothing that says people can play a role without attempting to experience a suggestion. Pretending will produce neural correlates to some degree.

- If people know they’ll be hypnotized later - they may ‘hold back’ with their imagination, artificially inflating the observed response.

TLDR - if you do a study - do a control group without hypnosis.

9.5 Summary and conclusions

Section titled “9.5 Summary and conclusions”A state theory of hypnosis posits that: (1) brain differences between hypnotized and non-hypnotized subjects will be observed with altered experiences and behaviors; (2) such differences are frequently observed in functional brain imaging studies; and (3) therefore, research supports a state theory of hypnosis. Yet observe (2) and therefore conclude (1) is correct is a logician’s error of affirming the consequent. Clearly, non-state theories also predict brain changes. After all, where else would such changes occur?

The state theory isn’t correct just because there are neural correlates. Psychology and socio-cognitive perspectives similarly account for and expect neural correlates. Research into ‘neutral’ hypnosis with just induction exists, but most of the correlates we’ve seen have been in normal bounds.

10 - An empirical-phenomenological approach to quantifying consciousness and states of consciousness: with particular reference to understanding the nature of hypnosis

Section titled “10 - An empirical-phenomenological approach to quantifying consciousness and states of consciousness: with particular reference to understanding the nature of hypnosis”Ronald J Pekka and VK Kumar

Not particularly interested in this section, I’m likely skipping this.

11 - On the contribution of neurophysiology to hypnosis research: current state and future directions

Section titled “11 - On the contribution of neurophysiology to hypnosis research: current state and future directions”Adrian Burgess

I’m probably skipping this one too.

12 - The experience of agency and hypnosis from an evolutionary perspective

Section titled “12 - The experience of agency and hypnosis from an evolutionary perspective”In here, they’ll be talking about agency in hypnosis, leading us through…

- Evolution, genetics, and animals models of hypnosis

- Evolution of the brain

- The development of human attachment and our social environment

(I’ve gone full smartass writing notes on this chapter, but really, the source material is interesting. I’m a bit burnt out by the density of this book overall though.)

12.1 Evolution

Section titled “12.1 Evolution”Darwin out first with the idea of natural selection - where selection focuses on…

- Physical characteristics

- Characteristics related to the environment

- Can the organism get laid and make babies in the current environment

Darwin then extended their theory to sexual selection. It’s not just the cock in peacock that makes them want to reproduce - while the colorful feathers conjure copulation contemplation for a avian cloaca’in for a good time, these feathers are an indication of health, and will thus affect which birds get booty. (Instinct.)

Darwin also saw social instinct as important for reproduction. Your libertarian tech-bro may not only be too annoying to get laid, but their predilections for isolation may reduce their survival rates. Therefore, cognitive processes are important to evolutionary selection as well.

Unlike other species - humans shape their environment, and have been doing so for a long time. Originally 150,000 years ago, we sucked as hunters - with only a 20% success rate - we were better at gathering nuts and fruits than trying to grab a sentient snack. About 80,000 years ago, we begin to find evidence that humans began to use pointy, stabby things, and at about 30,000 years ago, we start to see the appearance of symbolic behavior (such as art and animal figurines.)

12.2 Integration of evolution and genetics

Section titled “12.2 Integration of evolution and genetics”In 1937, Theodosius Dobzhansky studied genetics - figuring out that each member of a species did not have identical genetics.

12.3 Genetics

Section titled “12.3 Genetics”Some genes turn on and off depending on both internal and external environmental factors.

12.4 Genetic influences on hypnosis

Section titled “12.4 Genetic influences on hypnosis”Ah. Here we go.

… Aw man. I already don’t like this. Back to summarizing for me though.

- If genetics influences hypnotizability, we’d see it as a stable trait.

- According to two studies, hypnotizability of twins is one of the most hereditary (similar) out of all measurable psychological qualities.

- If you’re like me - you’re already asking about the environment being a factor…

- Monozygotic (genetically identical) twins had much more similar hypnotizability than dizygotic twins

12.5 Animal hypnosis

Section titled “12.5 Animal hypnosis”If we see genetic predisposition for hypnosis in humans, we should also see this in animals… depending on how you define hypnosis for animals. The good news is - I have plenty of willing therian and furry subjects to try this out on.

Let’s get on with it - apparently some dude talked about hypnotizing chickens by drawing a chalk line around them back in 1646

From that time to the present, there have been a variety of stories of how alligators, rabbits, chickens and other animals could be immobilized, generally by rubbing or stroking the animal, although eye fatigue through fixation has also been used.

Apparently, this is similar to an ‘action pattern’ that ethologists have seen - if you immobilize yourself, your predator might be less interested in eating you, and you might survive. Apparently placing a stuffed hawk in front of a chicken will freeze them in place for 5 or 6 minutes. And here I thought I needed to buy a pocket watch. This leads us to an interesting conclusion that pocket watches have indeed been a natural predator for homo sapiens for the last 30,000 years.

As snarky as I am today - here is a demo of animal hypnosis.

12.6 Evolution of the brain

Section titled “12.6 Evolution of the brain”Allegedly, the expansion of our frontal lobes in an evolutionary sense gave us the ability to override our stimulus response.

They say it’s important, moving forward through the chapter to remember that…

- Our neuroplasticity is partially related to us having big brains

- Brains come immature out of the box and (hopefully) mature over the next 15-25 years

12.7 Hughlings Jackson

Section titled “12.7 Hughlings Jackson”In the 1800s, John Hughlings Jackson created and used two principles for his research pertaining to the brain and it’s evolution:

- “hierarchical integration through inhibitory control” - we’ve evolved to control and inhibit some responses - and reflexes

- “encephalization” - special control systems can be taken over by general control mechanisms. Activity in one part of the brain can reduce activity in another part of the brain.

12.8 Paul MacLean

Section titled “12.8 Paul MacLean”MacLean pointed out that from between reptiles to mammals, brains developed the ability to nurse, understand vocalizations, and play. The author of the article thinks it’s possible that our ability to respond automatically to social cues may have evolved before our ability to develop a sense of volition.

12.9 Hypnotic level of mechanisms

Section titled “12.9 Hypnotic level of mechanisms”Hypnotic suggestion may affect the “Paul MacLean” part of the brain, but not the “Hughlings Jackson” part. In the author’s study, they…

- compared highs to lows

- Both responded to a stimulus to startle them

- Highs said the stimulus was quieter after being given a suggestion for it

In another study - they tested pain action potentials with an EEG. Pain action potentials come in two parts - first one relating directly to the stimulus, and the second being the emotional reaction. Both of these responses happen in <250ms, so the test subjects are unable to cognitively separate them. They found hypnotic suggestion did not affect the first action potential, but it could reduce the second.

12.10 Sense of agency

Section titled “12.10 Sense of agency”There three levels of response:

- reflex (blinking)

- Fixed action patterns (like egg rolling in geese)

- planning

You might plan to take a sip of coffee, but if you’re engrossed in a task - taking that drink may not take active engagement, and could feel automatic. The movement component could exist independent from the “agency” component.

TLDR: The ACC’s probably involved in hypnosis and volitional responses. While they bring up the theory that there may be reduced processing in the cingulate (the part that connects the two lobes,) we should see some evidence of that with an EEG.

12.11 Attachment and internalized self-regulation

Section titled “12.11 Attachment and internalized self-regulation”Since peak hypnotizability happens between the ages of 8-12, this may be related to cortical development, including their sensitivity to social influence.

The TLDR of this section is self-regulatory functions are still developing during this young age. Hypnotic response may be related to automatic response to social influences.

12.12 Evolutionary advantage to hypnosis

Section titled “12.12 Evolutionary advantage to hypnosis”Hypnotizability may be related to the ability to self-regulate - which would have evolutionary advantages.

12.13 Summary and Conclusion

Section titled “12.13 Summary and Conclusion”- There’s evidence (correlations) that suggest a genetic predisposition for hypnotic response

- We still don’t know what environmental conditions could influence gene activation modifying hypnotic response

- Hypnosis is likely involved in the interface between the limbic and neocortical systems. (The ACC is important.)

- Hypnosis may be related to the development of societal attachment

13 - To see feelingly: emotion, motivation, and hypnosis

Section titled “13 - To see feelingly: emotion, motivation, and hypnosis”Erik Woody and Henry Szechtman

13.1 Behavior and experience in hypnosis

Section titled “13.1 Behavior and experience in hypnosis”Academic scales of hypnotic response measure motor responses and feelings of volition, but measurability does not necessarily correlate to usefulness. The attribution of volition matters much more in a motor suggestion than a hallucination suggestion. The important part of this all is more about the subjective (not objective) experience - changes in volition and reality.

13.2 Feelings of knowing

Section titled “13.2 Feelings of knowing”Feelings of volition are more related to emotion than they are grounded in reality. William James said the sense of reality is closer to emotions than anything else. People with classic handwashing behaviors of OCD may be aware that they just washed their hands, but may not have the feeling of knowing they just washed their hands.

For OCD sufferers, knowing objectively does not translate into believing subjectively.

Some behavior and delusions come from changes in felt experience, where the opposite can be true as well - subjective experiences can be strong enough to override objective evidence.

13.3 Hypnosis and feelings of knowing

Section titled “13.3 Hypnosis and feelings of knowing”Suggestions in highs can resemble psychopathological symptoms.

Indeed, Kihlstrom (2006) characterized hypnosis as involving two essential qualities: ‘involuntariness bordering on compulsion’ and ‘conviction bordering on delusion.’

You could think of OCD and hallucinations in hypnosis as having opposite mechanisms in some cases - in OCD, a stimulus is present but a feeling of knowing is absent. On the flip side, hypnosis generates that feeling without a clear stimulus. Positive and negative hallucinations could be attributed to modifying feelings of knowing - either augmenting or diminishing them. When we pressure subjects to say something untrue - it may not just be compliance, but we may have genuinely altered their feeling of certainty - which can be modified with the non-hypnotic suggestion to “be honest” in their response. Explicit (intentional) perception can be split into two parts - an ‘overt’ cognitive component and ‘covert’ affective (emotional) component.

13.4 Approach to deriving a neural model of hypnosis

Section titled “13.4 Approach to deriving a neural model of hypnosis”Here’s what the authors want to ask…

- Does hypnosis work by altering the ‘feeling of knowing?’

- What naturally occurring conditions let feelings override sensory input and objective information?

- Assuming the brain can do this - what does hypnosis do to create these guiding feelings and conditions?

13.5 When feelings are enough

Section titled “13.5 When feelings are enough”If we simplified the brain into a gradient of neural complexity based on an evolutionary perspective, we might get something like…

- Reflexes, simple wiring, generally inflexible

- Mid-complexity systems. These depend on environment and genetics. Feelings (and the target of this article) lie here.

- Complex, fancy brain circuits with many inputs - “language, evaluation of alternatives, decision making, planning, reasoning, abstract thoughts…”, generally flexible

Usually - the nervous system works together with the rest of our brain. However, there’s a push-pull between these systems depending on circumstances. Say - if we’re pushed around at a party and set off balance, we might immediately engage our reflexes, experience a moment of being pissed off at being disrespected, and look over and calm ourselves the fuck down when we notice the guy is piss drunk and 6’8”. In other circumstances, if we were running away from someone late at night from an underpass, our resources would be automatically shifted to our limbic systems to book ass at the cost of mental flexibility.

13.6 The emotive nature of hypnosis

Section titled “13.6 The emotive nature of hypnosis”Mammalian societies have benefitted from a dominance hiearchy. Primates, are “easily seduced by confident, charismatic leaders. (Wilson, 1975)” They suggest that the hypnotic subject is “essentially that of a subordinate… with the hypnotist assuming the role of a dominant individual.”

According to Jaynes (1976)…

- Inductions often include a narrowing of focus to the hypnotist’s voice, suppressing your internal narration.

- Hypnotists are often presented as powerful and “larger than life.”

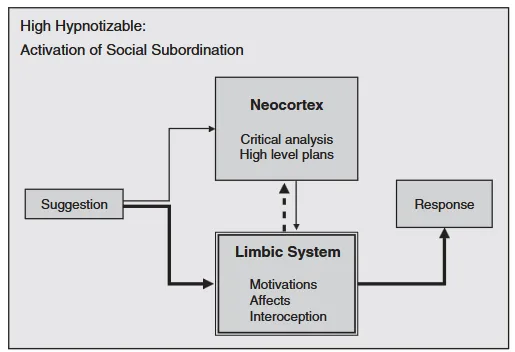

More modern ideas on hypnosis from Banks and Farber (2002) griped that in an academic setting, we’re ignoring a potent tool - dominance and subordination, much in the same way leaders or priests wield their power. They say the activation of this limbic-based system of subordination suppresses “prefrontal contributions to information processing,” much like trance logic where we stop actively questioning what the hypnotist is saying. They emphatically highlight that this is not rapport, compliance, or rational persuasion. This is a primal reflex. “From an evolutionary point of view, the capacity for such entrainment had considerable survival value (1975.)“

13.7 Model of hypnosis and neurology of interoception

Section titled “13.7 Model of hypnosis and neurology of interoception”They split ‘highs’ and ‘lows’ into two groups:

- Lows process hypnosis ‘normally’ through neocortical and subcortical inputs with reduced limbic activity. Or - put more plainly - these ‘lows’ are the people that go “uh, nah… my arm isn’t heavy, but thanks for asking.”

- Highs process hypnosis through their limbic system, fired up by subordination - where the limbic system feeds information to the neocortex, bypassing critical thought, motivating them through an affective state. The “HOLY FUCK MY ARM IS MOVING” people. The neocortex doesn’t have a chance to challenge the hypnotist’s bullshit.

We suggest that the motivational/affective state primed in the highly hypnotizable subject is one related to maintenance of social hierarchy and in particular to the appraisal and maintenance of subordinate status in a dominant/subordinate relationship.

All right - it’s a spicy take - but some personal notes on where this works:

- Stage hypnosis and televangelists.

- Hypnokink.

- Doctor patient relationships.

- A street hypnotist that’s got that rizz. (Fuck. Am I too old to say rizz?)

- Dave Fucking Elman and Milton Fucking Erickson.

- “In a moment, when I snap my fingers, you will close your eyes, and drop down into a deep trance for me.”

13.8 Conclusions

Section titled “13.8 Conclusions”Whew, okay. That was a rant. Back to the chapter…

The authors wanted to close with:

- Emotive/affective components of hypnosis need some TLC on the academic side.

- It could be helpful to think of hypnosis as a leftover from our evolution as a pack animal.

- It’d be a good idea to relate phenomena to “characteristics of underlying mental systems.”

14 - States of absorption: in search of neurobiological foundations

Section titled “14 - States of absorption: in search of neurobiological foundations”Ulrich Ott While this chapter does not deal only with hypnosis - absorption is often seen as a valuable component in the hypnotic experience - both for recreational and therapeutic value. Being absorbed in something (a book, watching twitch) happens all the time, not just in hypnosis.

I was hyped to learn something going into this chapter - I’m less excited when actually reading it. It feels very “we measured stuff and looked for correlates.” I’m probably just a bit worn out from reading something so dense and out of my league.

14.1.1 Tellegen’s Absorption Scale and related inventories

Section titled “14.1.1 Tellegen’s Absorption Scale and related inventories”Tellegen and Atkinson unveiled their Tellegen Absorption Scale (TAS) for subjectively measuring absorption.

After a quick google search - looks like Kihlstrom originally shared the scale, but the University of Minnesota Press asked them to remove it “so as not to compromise their validity.” 🧂

Before I get on to a rant - Tellegen found six factors…

- Stimulus response. Does that sunset blow your mind, dude?

- Synesthesia. Music to visual patterns.

- Enhanced cognition. I can sense the presence/auroa of someone.

- Oblivious/dissociative involvement. I forgot I was doing anything but reading Vreahli’s bullshit.

- Vivid reminiscence. Re-experiencing something. Kinda like hypnosis and revivification.

- Enhanced awareness and mystical peak experiences. (This may be unrelated, but entrancement is one of the 27 emotion categories identified at Berkeley. But ya know… social sciences.) For once, the article isn’t behind a paywall.

They mention…

- There’s a high correlation between factors in general - you should avoid using subscales.

- There’s a high correlation to hypnotic susceptibility.

14.1.2 Self-transcendence scale

Section titled “14.1.2 Self-transcendence scale”Unlike the TAS, Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory is more interested in the biological correlations of personality. They tried to connect seeking novelty, harm avoidance, and reward dependence to neurotransmitter systems (as personality dimensions.) On the side - the TCI-ST (self transcendence) has the following subscale components.

- ST1 - creative self-forgetfulness vs self-consciousness. “I was so absorbed I forgot where I was.”

- ST2 - transpersonal identification vs personal identification. “I’m one with mother earth, man.”

- ST3 - spiritual acceptance vs rational materialism. A sixth sense, or past lives.

14.1.3 Transliminality scale

Section titled “14.1.3 Transliminality scale”The TS (Transliminality scale), originally taken from the TS, has to do with mystical, paranormal, and magical thinking.

14.2 The disposition to become absorbed: genetic influences

Section titled “14.2 The disposition to become absorbed: genetic influences”I’m going to TLDR this section since I don’t think the nuance is particularly useful for my purposes. I want to politely disagree with some of the broad strokes the author makes, but it’s more likely that I just don’t have time to sit down and fully understand the material. (EG - there’s more hereditary influence on women than men, but it doesn’t talk about whether or not personality responses from women have in general less variance, for whatever reason.) FWIW, these are reasonably large studies compared to hypnotic analysis… where a hypnosis study would have 30ish people (ugh)… these analysis include more than 2,000 people since it’s just a survey.

- Studies suggest that genetics may have more to do with absorption than environmental influences (And I’m only now realizing that there’s some possible fallible logic of “if it isn’t environment, it must be genetics” or vice versa)

- The TCI-ST showed the highest genetic correlation of all 7 dimensions.

- The sample sizes of molecular level genetics studies are so small it’s hard to draw any conclusions, but very few correlations can be seen

14.3 Psychological markers of high absorption

Section titled “14.3 Psychological markers of high absorption”- There may be an association between high absorption and cardiovascular cardiovascular responsiveness to stress, baroreflex stimulation (which I had to look up, wtf) and yoga training

- Absorption scores are correlated with more “flexible attentional styles”

14.4 States of absorption during hypnosis and meditation: new theories and findings

Section titled “14.4 States of absorption during hypnosis and meditation: new theories and findings”Measures of absorption will not have direct or comprehensive correlates to hypnotic scales like the PCI. (And this is where skipping Chapter 10 bites me in the ass.) The gist is that the absorption scales measure different components of the subjective experiences of hypnosis.

- The altered states of consciousness (ASCs) have similarities between hypnosis and meditation. They also see similar activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) between the two contexts.

- Hallucinogens and antipsychotic drugs target serotonergic (5-HT2a) and dopaminergic systems, associated with the absorption trait. Self-reflective cognitive facilities are reduced during hallucination - in both hallucinogen induced and acute psychotic states.

- The brain regions involved in absorptive states may play a critical role in hypnosis, and experientially this may be a core component. Highs show more ACC ‘conflict’ activity than lows. One idea is that this could be an indication of decreased attentional efficiency, or the other idea is that this could be a compensatory for a hypnotic subject’s suspended cognitive control functions. They also talk about decreased coupling again in highs.

- Hypnosis could be seen as a type of guided meditation, due to their similarities in subjective experience and physiological changes.

14.5 Future perspectives

Section titled “14.5 Future perspectives”- Measuring neurophysiological correlates with FMRI in hypnosis and meditation sucks - it’s uncomfortable and loud when the FMRI is on.

- To measure this - they suggest finding subjects that are good at entering into these states even when distracted.

- We could study training absorption - such as through Trataka meditation (basically, focusing and staring at a thing, traditionally a candle.)

- Interestingly and ironically, biofeedback training can interfere (be distracting) to absorption.

15 Time distortion, and the nature of hypnosis and consciousness

Section titled “15 Time distortion, and the nature of hypnosis and consciousness”15.1 Behavior and experience

Section titled “15.1 Behavior and experience”- The interesting phenomena in hypnosis may be more the subjective experience than objective measurable behavior. For instance - we can either ask someone to act as if they were hypnotized and see a chair as empty, or have a hypnotized person actually see a chair as empty where their friend isn’t there. Isn’t the subjective experience of more compelling and worthy of study?

- There are strong social influences in hypnosis, but we’ve studied those elsewhere.

15.2 Searching for a genuine experience

Section titled “15.2 Searching for a genuine experience”- A ‘simulator’ group is common in studies - so we can separate between the hypnotic and compliance components.

- If we have someone see a color in hypnosis, there’s two questions… If we do brain scans while they’re seeing the color, but it’s not as good as the real thing, are we really learning much about hypnosis? If the brain scan matches imagination, why should we bother if we’re just imagining?

- Maybe we’re wasting our time with neural correlates - figuring out subjective experience with a brain scan is likely a fruitless endeavor right now.

15.3 Perception without suggestion

Section titled “15.3 Perception without suggestion”- What’s intrinsic to hypnosis? Like - what’s different between imagination and hypnotic hallucination?

- We see time compression spontaneously after a session - no need to directly suggest it. Simulators don’t produce this effect, so we know subjects are doing something beyond compliance.

15.4 Is hypnosis the cause of time distortion?

Section titled “15.4 Is hypnosis the cause of time distortion?”- Weirdly - there is no correlation between how much people underestimate the time they spent in hypnosis to how easily they respond.

15.5 Do amnesia and absorption distract from timing?

Section titled “15.5 Do amnesia and absorption distract from timing?”- Spontaneous hypnotic amnesia does not seem to be correlated to the amount of time distortion.

- In highs, when reading them a boring story after induction, they had substantial time distortion. They did not experience the same time distortion without this hypnotic context.

- Outside of hypnosis, high attentional demand correlates to time underestimation.

- Since time underestimation does not only occur in hypnosis, this will dilute measurement. Also, the mental workload of the hypnotic state may be the cause of time underestimation itself.

15.6 Hypnosis and mental workload

Section titled “15.6 Hypnosis and mental workload”- Adding workload to high hypnotizable people in hypnosis did not increase the time underestimation - in fact it appeared to reduce it’s effect. (They’re not sure what’s causing this… but they draw the conclusion that it’s not just cognitive load causing time underestimation.)

15.7 Hypnosis and the internal clock

Section titled “15.7 Hypnosis and the internal clock”- Time perception researchers assume that underestimation under load comes from the reduction in resources to notice time, like counting ‘ticks’ on a clock.

- Prospective (tell me in 2 minutes) estimates are usually longer and more accurate than retrospective estimates.

- In hypnosis - prospective estimates were 60% longer, and retrospective estimates were 32% shorter. (Time feels like it passes more quickly in hypnosis.)

15.8 Hypnosis and brief interval assessment

Section titled “15.8 Hypnosis and brief interval assessment”- The author asked subjects to measure the length of some computer generated beeps. They pressed the button about 17% longer in hypnosis, and underestimated the length of time by about 19% as compared to control groups.

15.9 Consciousness and its modification

Section titled “15.9 Consciousness and its modification”- Again, the ACC is involved in hypnosis and hallucinations (both hypnotic and with psychological disorders.)

- Schizophrenic hallucinations and hypnosis have neurophysiological similarities - as shown in PET scans.

15.10 Consciousness and the clock

Section titled “15.10 Consciousness and the clock” (Not sure if Flavor Flav is a hypnotist but he sure does have the clock for it.)

(Not sure if Flavor Flav is a hypnotist but he sure does have the clock for it.)

- Parkinsons disease and schizophrenic subjects show impaired time perception abilities.

- The time distortions of hypnosis could have related causes - some sort of disruption of the ‘consciousness cycle’ of the “septo-hippocampal” system. I am totally going to pretend I know what they’re talking about.

15.11 Self-generated consciousness and the clock

Section titled “15.11 Self-generated consciousness and the clock”- The author says that people susceptible to hypnosis could be unaware that they are avoiding reality checking - commonly associated with activity in the ACC.

- Subjects that were able to vividly (by self report) detach more effectively (measured by self-report of avoiding outside distraction) into a beach scene, instructed as waiting for a friend as they held on to a clock, displayed the greatest time distortion. (This could be a fun little thing to do with your recreational subjects!)