The Practice of Cognitive-Behavioural Hypnotherapy (WIP)

Donald J. Robertson

Unlike CBT, hypnosis is seen as an adjunct to therapy, not a therapy itself.

Acronyms

Section titled “Acronyms”- CBT - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CBH - Cognitive-Behavioral Hypnotherapy

- NSH - Negative Self Hypnosis (worry, rumination)

Part 1 - The Cognitive-Behavioural Approach to Hypnosis

Section titled “Part 1 - The Cognitive-Behavioural Approach to Hypnosis”Chapter 1 - Introduction to cognitive-behavioural hypnotherapy

Section titled “Chapter 1 - Introduction to cognitive-behavioural hypnotherapy”- CBH is not just integrating CBT with hypnosis, but rethinking hypnosis through a CBT lens.

- Behavior therapy, the precursor to modern CBT, was developed by Joseph Wolf - originally called ‘hypnotic desensitization.’ There were others, but they were thought of as hypnotic interventions minus the hypnosis label.

Of course, hypnotism is essentially a cognitive procedure: hypnotic suggestions are intended to evoke ideas (cognitions) that lead to certain desired hypnotic responses.

Personal thought - a comedian is to comedy as a hypnotist is to hypnotic trance and hypnosis. There’s no ‘comedy’ state, but comedy is real.

Their Hypnotic Mindset model is based on the cognitive-set described by Barber.

- Recognition. Induction as a cue to act favorably towards hypnosis (selective attention, implementing suggestions.)

- Attribution. Accurately attributing responses to imagination and expectations, rather than just voluntary compliance.

- Appraisal. See hypnosis as an opportunity, not a threat. (Uninhibited.)

- Control. Confidence in fulfilling the suggestions, as well as confidence in automatic response given the right mindset. Self-efficacy and response expectancy.

- Commitment. Accurately estimating effort - not ‘trying to hard’ or ‘just waiting.’

Roles (Sarbin) may give ‘schema’ (Beck) to responses.

CBH should have…

- Psychopathology. A cognitive-behavioral understanding of the problem.

- Treatment rationale. A CB solution approach.

- Hypnosis. A CB reconceptualization of hypnosis and procedures.

Albert Ellis, founder of rational-emotive behavioral therapy (REBT,) suggested that if we engage in harmful rumination and it causes unwanted effects, we can use the same tools of rumination to negate those effects. (Regarding auto-suggestion.)

In a study - CBH was 70% more effective than CBT alone.

Interesting…

They “rearrange themselves” to get into the right mind-set and orientation, and shift their focus of attention on to the most relevant cues, probably the voice of the hypnotist and the location of the sensations being suggested. They adopt the appropriate mind-set in order to be able to pass the first test, that is, to respond to the hypnotic induction technique. It’s important to realise that means hypnotic subjects enter hypnosis, at least to an initial extent, just before the hypnotic induction rather than after it; that is, in preparation rather than as a consequence.

(There’s a solid smackdown interesting take on Ericksonian approaches in therapy around p19 worth a read.)

Hypnosis has advantages over just CBT…

- Response expectancy because of that hypnotist swag vs just therapy.

- Relaxation is a cool bonus.

- Learning benign dissociative skills.

- “Dehypnosis” strategies - which can be applied in hypnosis… Then applied in an anxiety loop.

- Hypnosis enhances imaginative intensity.

- Hypnosis supports experiencing emotional states.

- Hypnosis expands your toolkit.

- Training autosuggestion is a good tool to have.

- Hypnotherapy is a “creative melting pot.”

- Hypnotherapists have skills for making therapeutic recordings.

There are more specific enhancements in imagination in CBH.

- Maladaptive behavior is more clearly identified.

- The client is exposed to a range of situational cues.

- Greater engagement, including emotional.

- Imagery may allow the client to become aware of behavioral and cognitive patterns.

- Imagery behavior, with practice, allows selective attention.

Meditation as ‘dehypnosis’ (exiting a maladaptive cognitive loop) is also a benefit. Seeing your own thoughts as a “movie,” or uh - learning to ignore your hypnotist as you would discard a suggestion, has benefits.

- Hypnosis is behaving ‘as if.’

- Dehypnosis is behaving ‘as if not.’ Simply being aware like a movie, not getting lost in the story.

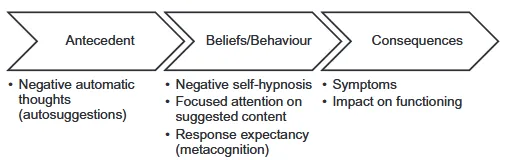

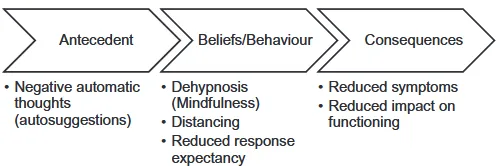

Including these tables to show how a CBT approach sees this.

- Suggestions can encourage compliance with a meditation practice.

- Suggestions can encourage a patient (healing) mindset, where healing is natural.

- Suggestions can be given for acceptance.

- Hypnosis can avoid identification with thoughts and feelings.

- Hypnosis can increase acceptance of thoughts and feelings.

- Suggestions can improve the perception that negative thoughts are transient and unimportant.

Can combo hypnosis with mindfulness meditation to…

- Do exposure therapy (covert behavioral rehearsal.)

- Cue relaxation.

- Desensitization.

- Regression, such as in PTSD treatment.

- Suggestion to help clients tolerate the discomfort and repetition in exposure therapy.

“Imagine that you are transparent, and disturbing thoughts and emotions cannot penetrate you or have any power to control your actions.” Suggestions can be used to weaken (negative) suggestions, hypnosis to nullify (negative) self-hypnosis.

The book will cover four main traditions of CBT as CBH.

- Stress inoculation training (SIT.) Training hypnotherapy, mindfulness, and ‘dehypnosis.’

- Exposure and response prevention (ERP,) for more severe cases.

- Problem solving therapy (PST.)

- Cognitive therapy. Examining faulty threat appraisals, distortions, using distancing and dehypnosis.

Chapter 2 - James Braid and the original hypnotherapy

Section titled “Chapter 2 - James Braid and the original hypnotherapy”When we understand Braid’s position on hypnosis, it’s relationship to CBT becomes obvious. They saw hypnosis as focusing on a single idea, expecting a response, and the effects of mind over body.

Originally - Braid introduced the term hypnotism as short for neuro-hypnotism, the “sleep of the nervous system.”

Braid facts:

- They never referred to the conscious mind - hypnosis was a form of focus and imagination.

- He did not believe trance was involved in hypnosis.

- He thought of suggestion as “dominant ideas.”

- He thought hypnosis had more in common with yogic meditation than Mesmerism.

- He regretted introducing the term “hypnotism,” as hypnosis is unrelated to sleep.

- Hypnosis could only be done consensually - people reject what is objectionable.

- His positive definition had to do with focusing on an idea and expecting an outcome.

The book suggests a ‘return to Braid’ in hypnotherapy because…

- The confusion surrounding hypnosis comes from Mesmerism, not hypnosis.

- Braid embraced hypnosis as a “common sense” approach to therapy.

- Their approach is simple and largely compatible with CBT.

- Braid saw psychopathologies such as negative ‘automatic thoughts’ and hysteria as hypnotic in nature.

Braid worked with William Carpenter and based his ideas on his ideo-motor theory. This is similar to cognitive-behavioral concepts, where ideo-motor responses are motor responses to ideas.

Franz Mesmer and Victorian nostrum remedies

Section titled “Franz Mesmer and Victorian nostrum remedies”According to the author, hypnotism did not originate from Franz Mesmer, who believed he could control the magnetic forces in others with his body and mind. Animal magnetism and mineral magnetism were to separate ideas - and Braid suggested mesmeric responses were due to expectation and suggestion. Marquis de Puysegur, following in Mesmer’s footsteps, developed a more relaxed term of “artificial somnambulism” and tried to create it’s effects. The unfortunate downside of this is hypnotism has since been seen as related to sleep.

The scientific community was (rightfully) skeptic of Mesmer’s claims, and included some of the earliest placebo-like control trials. Faithful followers of Mesmer believed the control was in the hands of the Mesmerist/operator, and their model did not have space for ‘self-magnetism.‘

James Braid, the father of hypnotherapy

Section titled “James Braid, the father of hypnotherapy”Braid, while initially outwardly combative and skeptical against the idea of Mesmerism, tempered his point of view after seeing a demonstration where he himself slid a pin between a subject’s nail and their finger, remaining mesmerized. He made the motto of his first book…

“Unlimited scepticism is equally the child of imbecility as implicit credulity.” -Professor Dugald Stewart

At this point, Braid asked the mesmerists to take a more scientific approach in their studies. Stewart saw that mesmeric response could be a byproduct of focused attention, from observing Mesmer’s techniques of fixation. Braid’s initial attempts at inducing this included eye strain, but he later found it to be unnecessary. With Braid’s new techniques, he was able to create similar effects faster than mesmerists - to the point where some of them suggested he was naturally a Mesmerist himself. (Braid disproved this by training others in his technique, getting similar results.)

Hypnotism may have been introduced in concept by braid as neurological inhibition (‘nervous sleep’) created by prolonged selective focus.

The battle with Mesmerism

Section titled “The battle with Mesmerism”Originally, Braid coined hypnotism to differentiate himself from the esoteric beliefs of Mesmerism. The Mesmerists, instead of accepting Braid’s position, hypothesized Braid had found a ‘new agency,’ and both mechanisms existed.

Braid and yogic meditation

Section titled “Braid and yogic meditation”Braid found yogic meditation similar to his idea of hypnotism, but unlike mesmerism, and used this as evidence against mesmerism.

William B. Carpenter and the ideo-motor reflex

Section titled “William B. Carpenter and the ideo-motor reflex”Braid worked with Professor William Benjamin Carpenter, working together to scientifically examine (dismantle) mesmerism. Carpenter came up with the idea of the “ideo-motor reflex,” which Braid assimilated into his work. Ironically, the two of them were seen as a ‘threat’ to mesmerism.

Who discovered hypnotism?

Section titled “Who discovered hypnotism?”Abbe de Faria and Alexandre Bertrand seemed to also reject magnetism, despite being mesmerists, but did not appear to follow Braid’s scientific approach.

Braid’s theory of hypnotism

Section titled “Braid’s theory of hypnotism”Braid, in the end, saw hypnosis as a mental state rather than a physical response, reaching the conclusion when a patient could not reach said state when they did not have the mental capability to focus due to their fever. When explaining their concept of selective attention, they highlighted attention and inattention work hand in hand. For example, focusing on the feeling of your phone or mouse in your hand requires temporarily excluding awareness (inattention) of other thoughts. Continuing with this thought, we could define rumination and worry as NSH (negative self hypnosis,) beginning to link their theory with modern CBT.

Historically in the 1850s, the terms hypnotic trance and catalepsy were sometimes interchangeable. Braid, in their own writing, used the terms catalepsy, trance, and hibernation as synonyms. The only time they used the term trance was in patients that would enter this ‘death-like’ yogic meditative state. In later writings, they called an even ‘deeper’ stage of sleep the hypnotic coma. Trance was a state of relaxation resembling an artificial coma.

The author highlights that the term and concept of trance has been watered down in modern practice, usually doing more harm than good. It encourages passive rather than active engagement, as well as creates unrealistic expectations of the experience.

Braid highlighted that hypnosis is in opposition to sleep - as it requires “prolonged conscious attention,” rather than letting go of that control. It is interesting to note that most spontaneous amnesia can be suggested away - therefore the subjects are sometimes amnesic, but not unconscious. Unfortunately, due to hypnosis often being seen similar to sleep, Braid had to often had to demonstrate that therapeutic effects could be created even without this expected complete lack of awareness and control.

Braid and hypnotic induction

Section titled “Braid and hypnotic induction”This section quotes James Braid’s first technique in full - which can be found in Neurypnology; or, The rationale of nervous sleep, considered in relation with animal magnetism on page 27, right at the start of Chapter 2. I recommend you go read it from the linked source for the full-flavor experience.

Given this - Braid initially broke hypnosis into two stages - first “nervous arousal and increased awareness,” then catalepsy, “limited consciousness,” “torpor,” and amnesia. They later found these ‘states’ to be different forms of hypnotism, rather than different stages or layers in a process. They later mentioned that these conditions can be trained and brought back through imagination alone. In opposition, they also stated…

… the most expert hypnotist in the world may exert all his endeavours in vain, if the party does not expect it, and mentally and bodily comply, thus yield to it.

Braid’s observations leaned towards Kirsch’s response expectancy theories - where subjects expected something to happen (like tiredness,) and allowed them to happen. They also used to work in public, observing that when one subject responded strongly, other subjects would start to respond in kind. (See, CSTP.)

Braid’s theory of suggestion

Section titled “Braid’s theory of suggestion”Braid generally used simple suggestions, however he believed that hypnotists used effective rhetoric to create physiological responses much in the same way a story will evoke emotion, similar to what Sarbin theorized in the late 1900s.

Braid broke down suggestion delivery devices into the following:

- Auditory (via speech)

- Written

- Habit and association (EG - if you could see a finger touch your arm, but it never actually touched, you may feel tingles)

- Muscular - to quote the book ‘when they feel impressions which “call subjacent muscles into action”’

- Spontaneous associations - a precursor to indirect suggestion

Carpenter’s idea (which Braid followed) of the ideo-motor reflex (IMR) theorized that continued attention to an idea may cause automatic muscular responses. It’s detailed in the book - but it’s “basically the original neuro-physiological theory of hypnotic suggestion.” Interestingly - this idea was built upon towards the original definition of an ideo-dynamic reflex. Responses such as lacrimation, lactation, and salivation aren’t motor responses per-se, so the term ideo-dynamic response was used as a catch-all.

The author is keen to point out that we use the term ideo-dynamic far too loosely. It points to a specific explanation for a set of responses. Weitzenhoffer points to these as avolitional psychophysiological responses, differentiating them from communicated instructions and commands.

Braid also believed there was a two-way link between mind and body for these suggestions. For example - if you smile, you’ll likely feel a twinge of happiness, despite the fact that usually respond to happiness by smiling. (This might fall into Braid’s ‘muscular suggestion’ category.) You could also consider acting ‘as if’ in this category. Staring intently on something (EG, a pocketwatch) or relaxing back in your chair may cause focus or relaxation, respectively.

Earlier - with the smiling example, there was a theory of the “anatomy of expression.” Given this, Braid felt that it only makes sense that we could modify this, creating the same type of two-way bindings, leading to hypnotic triggers much like we see conditioned responses.

Similarly, Braid regularly mentioned a “law of habit and association,” similar to Pavlov’s conditioned responses. There’s this cool tidbit that suggests we can dilate capillaries with some practice…

For example, by placing his hand repeatedly in very warm water, someone may learn to remember the feeling, perhaps by attaching a cue or trigger word to it, and thereby induce dilation of the peripheral blood capillaries in the hand, a technique sometimes used in the management of headaches.

The book mentions that Braid saw hypnosis can enhance behavior modeling. (There’s a tale of a high-responder accurately imitating an opera singer’s abilities, but even the author admits skepticism is welcome, merely using the example to highlight it’s capabilities.)

Braid also felt that the way you say something was important when delivering suggestions. Their example asking someone to wait until they notice an animal, either in an upbeat or gave tone, and you’ll get a predictably lighthearted or dark response.

Thankfully, Braid was against the “imagination theory” that proposed hypnosis was merely imagination. He sought to highlight the interaction between body and mind, calling it “psycho-physiology.” They also suggested that cognition, behavior (muscle movement) and physiological sensations all work together to reinforce expectation, creating a sort of web (called a loop in the book) of feedback.

Braid and hypnotic therapy

Section titled “Braid and hypnotic therapy”While Braid and Carpenter realized that illnesses could be caused (or made worse) by ideo-dynamic responses, one of those components being cognition. In order to ameliorate these issues, they attempted to give suggestions that were contrary (healthier) than the existing ones. What they didn’t do was attempt to disrupt the existing “negative” self-hypnosis, creating or worsening the root cause.

Albert Ellis, the creator of REBT (Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy,) noted that autosuggestion may be very effective for removing “neurotic and psychotic symptoms,” as it is the same mechanism likely causing the issue. Similarly, Beck felt the ABC (Activation, Beliefs, Consequences) model of CBT lined up well with earlier autosuggestion models.

Wilkinson, a client of Braid, was quoted highlighting two components of hypnosis that were particularly therapeutic - trance (relaxation and dissociation) and suggestions. In some of Braid’s treatments, he’d leave patients to “rest in silence to maintain optimal relaxation,” something left out of common practice today. The author is careful to remind us that relaxation is only a response, but it is “not in any way essential to hypnosis.”

Braid noted two main conditions of hypnosis could be induced, “somnolence” and “tension.” Continuing with the idea that he would leave someone in a state for five to ten minutes, if one did not provide therapeutic benefit, he would try the other, and sometimes have positive results. Braid mentioned that we should distract attention away from the parts of the body we intend to “tranquilize.”

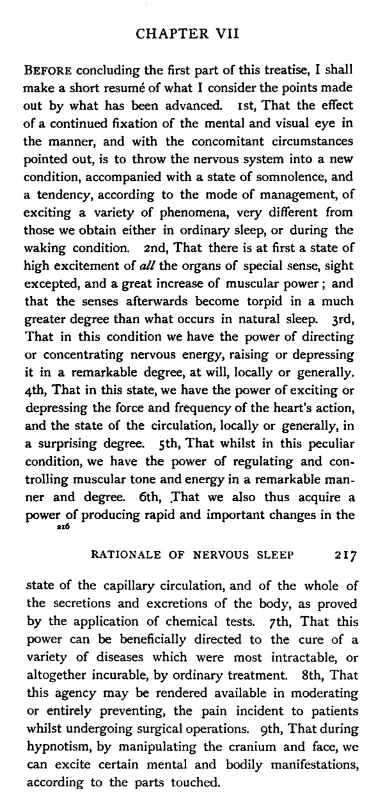

Braid summarized his findings in Neurypnology on page 217, available from the Wood Library Museum of Anesthesiology. I’ll list them out here…

- Eye-fixation

- Separate hypnotic conditions - excitement and torpor

- We can greatly modify this “nervous energy”

- Similarly, we can also modify the heart rate

- In addition, muscle tone (EG - catalepsy/rigidity/whatever you want to call it)

- And… physiological effects (EG - capillary action)

- Given all that, we can use these effects to “cure a variety of diseases most intractable…”

- We can use this to modulate pain during surgery

- We can “excite certain mental and bodily manifestations” through touch

Chapter 3 - Cognitive-behavioral theories of hypnosis

Section titled “Chapter 3 - Cognitive-behavioral theories of hypnosis”Most of this chapter feels like review for me of the book Clinical Hypnosis and Self Regulation. Don’t get me wrong, this chapter slaps - it’s helped me congeal the theories I’ve read about and organized concepts by researcher.

🦈🦊 There’s more than just cognitive vs state theory…

While the book mentions Hilgard’s neodissociation theory of hypnosis, they don’t go in to more modern state theory, as well as missing out on cold control. While it’s in the weeds for the scope of this book, and I agree with it’s sentiment, it would be unfair to so say that state theory was put on equal standing for our evaluation.

In addition, they miss out on cold control (a purely cognitive theory on hypnosis,) as well as the automatic imagination model. In the book’s defense, the automatic imagination model is in it’s infancy at this point, and cold control doesn’t neatly fit into the socio-cognitive model.

The state versus nonstate argument

Section titled “The state versus nonstate argument”Thankfully, state and non-state views on hypnosis appear to be slowly converging, and the fiery arguments in the 70s are cooling down. With that being said, this is a cognitive-behavioral perspective on hypnosis, and the chapter starts by highlighting the shortcomings of the state-based position.

A state based view on hypnosis generally includes…

- Inducing an altered state of consciousness called trance.

- Responsiveness is correlated to the depth of the trance. (A personal note - I do not personally see this in most modern state theory papers.)

- Some phenomena (like anesthesia, amnesia, and regression) require trance.

- Feelings of “absorption, dissociation, relaxation, or disorientation” are linked to trance.

Nonstate theorists see ‘trance’ as a byproduct of suggestion, not a special state. They list some counterarguments to state theory, which I’ve summarized here.

- Observations of trance are inferred on subjective reports, which do not require an altered state of consciousness (ASC).

- Brain imaging provides correlated, but not isomorphic evidence of state. (It’s unclear.)

- Effectiveness of hypnotherapy is not dramatically more effective than other therapies, like CBT.

- We only get a 20% boost in effectiveness after hypnotic induction. (It’s not 100%.)

- Motivational scripts (coaching response) are nearly identical to induction in effectiveness.

- All phenomena has been reported without a prerequisite induction.

- Feelings of trance are not unique to hypnosis, and correlate poorly to response.

- There is some, but not strong correlation with suggestibility tests and treatment outcome.

- The purported benefits of trance (EG strong expectation and absorption) are all normal things seen outside of trance.

- Neurological changes are not isomorphic with response, which doesn’t point to a single hypnotic state. (Similar to #2.)

The early history of the cognitive-behavioral position

Section titled “The early history of the cognitive-behavioral position”Behavioral theories on hypnosis trace back to Pavlovian conditioning, eventually leading up to Clark Hull’s research in the 1920s. However, bridging towards a socio-cognitive perspective, the author mentions Robert White - pointing out that…

Hypnotic behavior is meaningful, goal-directed striving… and is continuously defined by the operator and understood by the client.

This shifts our understanding from hypnosis being something that “happens” and towards an understanding focusing on social interaction and cognitive behavior. This gave Theodore Sarbin footing to suggest “trance depth” could be equated to a level of “role involvement” in being a “hypnotic subject.”

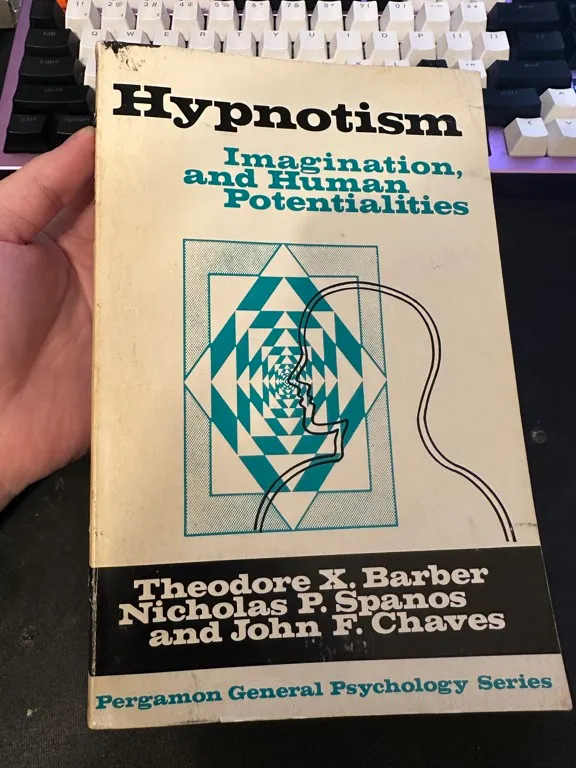

It’s weird how some of this shit “gets real” when you own a piece of history. The author mentions a book from 1974, written by T X Barber, Spanos, and Chavez, rejecting the concept of trance, a precursor to what is now known as the cognitive-behavioral theory on hypnosis.

From the book, they quote…

From the cognitive-behavioural viewpoint, subjects carry out so-called “hypnotic” behaviours when they have positive attitudes, motivations, and expectations toward the test situation which lead to a willingness to think and imagine with the themes that are suggested.

I still haven’t read it, but I purchased this book per the recommendation on Cosmic Pancakes. It turns out Kev Sheldrake (one of the authors of Cosmic Pancakes) is the one spearheading the automatic imagination model as part of their PHD, IIRC.

Anyway… back to the book.

They broadly split cognitive theories of hypnosis in to four main categories.

- “Roleplay” or role-enactment - Theodore Sarbin.

- Attitudes (cognitions) and imaginative involvement - T X Barber and co.

- Cognitive Strategies - Spanos.

- Response expectancy and response sets - Irving Kirsch and Steven Jay Lynn.

Sarbin and role-taking

Section titled “Sarbin and role-taking”Sarbin highlighted that hypnosis was like ‘acting,’ however this was unfortunately taken as trivializing the effects of hypnosis. On the contrary, Sarbin acknowledged that hypnosis can be an effective tool for making real changes, but so can constructed rituals (EG - shamanic experiences.) They also saw that there’s a gradient of absorption. EG - poor subjects are less engrossed than great actors.

From their perspective, hypnotic response is primarily determined by:

- Motivation

- Role-perception - what the subject thinks their role is as a hypnotic subject

- Role-taking ability - their ability to actively imagine or act “as if.”

They argued actors go through many of the same changes as hypnotic subjects… becoming dissociated from the crowd watching, experiencing time distortion, exhibiting selective attention, and sometimes displaying spontaneous amnesia.

They noted that different approaches to acting would have different responses:

- “Heated” methods, such as method acting where the actors try to create conditions (and an emotional state) to fill the role

- “Technical” methods, where actions are deliberate and calculated, but do not usually involve the actor’s internal experience

Sarbin saw imagination as role-taking behavior, or the famously quoted “believed-in imagining.”

The book provides a few studies highlighting that “heated” acting can create automatic physiological changes (EG, gastrointestinal distress in fear.)

Barber and cognitive-behavioral theory

Section titled “Barber and cognitive-behavioral theory”Barber, as part of a larger body of work, researched suggestion response with and without induction. While control groups working without induction or encouragement did perform the worst, people given motivational instructions responded just about as well as those that had received a traditional hypnotic induction. They found that defining the situation as hypnosis, using an induction, the suggestion wording, and the tone of voice (delivery) during hypnosis all affected outcomes. However, they also made the observation that this had more to do with the “cognitions and behavior” of the subjects themselves, the aforementioned components contributing to the subject’s mindset, thus affecting response.

They classified subject’s behavior types as follows:

- Negative. (I won’t do this, or this won’t work.)

- Passive. (Wait for it to happen.)

- Active-positive. (Thinking along and actively imagining.)

- Naturals. They just do this spontaneously.

- Trained. Those that need to be coached.

Their theory of hypnosis could be roughly simplified into the ABC model:

- Antecedents. Labeling the situation as hypnosis, dispelling myths, encouraging co-operation (“socialization”), presenting the induction, tone confidence.

- Beliefs. Expectancies, attitudes, and motivations. (Cognitive) Behavior. Actively imagining and working with the suggestions.

- Consequences. Hypnotic behavior and internal experience. They’ll report being hypnotized.

The book highlights that we can use this to infer that hypnosis does not depend on relaxation. They interestingly point to a study where they modified a script to work with both people instructed to relax, as well as those exercising on a bicycle. Both groups provided an induction responded better than those that were not provided an induction at all. This reminds me a lot of the information presented by Binaural Histoglog on the Valencia Induction.

The book notes the focus lauded for some of the positive effects in hypnosis may not actually be that helpful. This also lines up with my personal recreational experience.

The placebo effect and response expectancy (Kirsch)

Section titled “The placebo effect and response expectancy (Kirsch)”TLDR of the intro - effective placebo use is difficult, but quite powerful.

- Most treatments before the 20th century were placebo, but were still effective.

- Things like depression and anxiety respond well to placebo… less so than a broken leg.

- The placebo effect is strong enough to require control groups for in effectiveness studies.

- Much of the effects of antidepressants and psychotherapy can be attributed to active placebo. See Kirsch’s book, The Emperor’s New Drugs. (It’s a good read.)

- If you’re giving placebo pills for anxiety, make them green. Use yellow pills for depression. Red was least effective in both cases.

Surprisingly, a non-blind placebo can still be effective. In a study, they read the following before offering to give a placebo:

“Mr. Doe, at the intake conference we discussed your problems and it was decided to consider further the possibility and the need of treatment for you before we make a final recommendation next week. Meanwhile, we have a week between now and our next appointment, and we would like to do something to give you some relief from your symptoms. Many different kinds of tranquilisers and similar pills have been used for conditions such as yours, and many of them have helped. Many people with your kind of condition have also been helped by what are sometimes called ‘sugar pills,’ and we feel that a so-called sugar pill may help you, too. Do you know what a sugar pill is? A sugar pill is a pill with no medicine in it at all. I think this pill will help you as it has helped so many others. Are you willing to try this pill?” (Park & Covi, 1965)

Given this…

- Some people were convinced they were given (effective) active medication, even though they were prescribed sugar pills.

- Most surprisingly to me, only one person tapped out of the experiment.

- Not mentioned in the book, but the ritual of care may have been the most effective element.

It’s not a hard shift in perspective to see both psychotherapy and hypnotherapy as non-deceptive placebos.

The short version is - predictions affect outcomes, and we can shift those predictions. I’ve written a recreational take on this model here. The important bit to remember is that people could imagine along with suggestions that their arm is getting lighter, with no expectation that their arm would rise, and it’s likely their arm would not begin to rise.

Moving to involuntariness of response, it’s hard to tell if our responses are voluntary in everyday life, not only in hypnosis. EG - if you felt something crawl up your arm, would you jump and swat it automatically, and was it volitional looking back? They cite Simon Says as a solid example of this - where there are components of voluntary compliance, but automatic response when someone doesn’t say Simon Says.

In addition to expectation, they also developed the idea of “Response Sets.” Expectation alone may not be enough to illicit response. EG - if we expect an arm to rise on it’s own, it may take a sufficient amount of “lightness” being imagined for it to begin to happen. Kirsch puts it pretty well himself…

Actions are prepared for automatic activation by response sets. Response sets are comprised of coherent mental associations or representations, and refer to expectancies and intentions that prepare cognitive and behavioural schemas (i.e., knowledge structures), roles or scripts for efficient and seemingly automatic activation. Expectancies and intentions are temporary states of readiness to respond in particular ways to particular stimuli (e.g., hypnotic suggestions), under particular conditions. They differ only in the attribution the participant makes about the volitional character of the anticipated act. That is, we intend to perform voluntary behaviours (e.g., stopping at a stop sign); we expect to emit automatic behaviours such as crying at a wedding or, more relevant to our present discussion, responding to a hypnotic suggestion. (Lynn, Kirsch & Hallquist, 2008, p. 126)

Conclusion: a metacognitive model of hypnosis

Section titled “Conclusion: a metacognitive model of hypnosis”There’s a bit of nuance to the author’s cognitive set for effective hypnosis that I’m going to skip over, but here’s the TLDR.

- Recognition of the situation as hypnosis, understanding the suggestions, and experiencing them in an environment amenable to hypnosis.

- Appraisal - accepting suggestions.

- Attribution - this is therapy oriented, but they’d prefer the suggestions to be in response to the subject’s own imagination, rather than a volitional response or the hypnotist’s words.

- Control - the subject is confident they can both be a good subject as well as respond to the suggestions.

- Commitment - being motivated, “neither rushing nor avoiding being hypnotised.”

The book provides a questionnaire for subjects, with the request to rate them by percentage of how much they agree with something. Here’s a summary with a recreation-compatible spin…

- (Recognition) I deliberately and readily focused on and followed suggestions.

- (Attribution.) My hypnotic responses were because of my imagination and intention, rather than in direct response to the hypnotist.

- (Appraisal.) I felt safe.

- (Appraisal.) I wanted to do this, and I wanted to respond.

- (Control.) I was confident I could be a good subject and follow suggestions.

- (Control.) I expected suggestions to be effective.

- (Commitment.) I wanted to be here and experience this.

- (Commitment.) I was patient and diligent in following suggestions, expecting a response.

Part 2 - Assessment, Conceptualization, and Hypnotic Skills

Section titled “Part 2 - Assessment, Conceptualization, and Hypnotic Skills”Chapter 4 - Assessment in cognitive-behavioral hypnotherapy

Section titled “Chapter 4 - Assessment in cognitive-behavioral hypnotherapy”Reminder - I’m a recreational hypnotist. I won’t be covering this in detail, as I don’t want to tell people how to do therapy, much of this does not apply to my intentions, as well as to encourage an actual hypnotherapist to consult the (quite good) source material.

Takeaways:

- Most therapists use 50 minutes in assessment. If you’re doing something big, take your time.

The therapeutic relationship

Section titled “The therapeutic relationship”p120 Developing the ‘working alliance’ includes bonding, trust, and agreement on goals and tasks, the latter two often being overlooked.

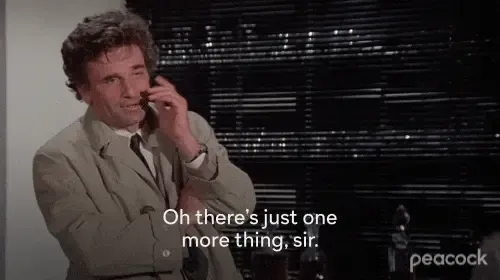

Planning includes defining the main problem, why it’s a problem, the main goal, what we’re going to do (together,) and why we think it’ll work. Their (TX Barber’s) take on CREAM is TEAM - trust, motivation, expectations, and attitude for maximizing response. I dig their approach to how to ask questions about the issue… which I’m going to steal and coin the Columbo Strategy.

The typical cognitive-behavioural therapist is rather like the television detective Columbo whose trademark strategy, akin to a modern Socrates, was to feign befuddlement and ask carefully chosen questions to get to the bottom of things.

-The Practice of Cognitive Behavioral Hypnotherapy, P122

They also provide the single worded technique for asking questions…

If you were allowed only a single word to describe your problems, what would that word be?

-The Practice of Cognitive Behavioral Hypnotherapy, P122

If you’re in the know about parrot-phrasing and nominalizations, you’ll know exactly how to apply this recreationally.

Case formulation in cognitive-behavioral hypnotherapy

Section titled “Case formulation in cognitive-behavioral hypnotherapy”Creating a theory for a CBT treatment plan involves creating a working theory with the client based on what we know in psychology. Apparently, diagramming the issue can become as complex as looking at a circuit diagram. However, they suggest beginner therapists start with a simple ABC approach. In added nuance, this diagram is separate from a diagnosis.

Goal definitions of therapy can be SMART - specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-limited. However, this is not always appropriate, specifically in cases when trying to modify affective or cognitive qualities, rather than behavior.

Formulation models are usually situational (a specific situation) or longitudinal/developmental (exploring the development of the issue over time.) Conceptualizations can also be descriptive (analytical,) explanatory (describing the function,) or chronological - describing the temporal element of the problem. Triggers can be environmental, interoceptive (bodily sensations,) or cognitive.

Doing systematic desensitization can involve modifying the time distance (how soon to an interview,) spatial distance (a block from a cranky dog, right next to the fence,) or content (rehearsing an interview in a mirror, to a friend, etc.) Cognitive behavioral hypnotherapy can separately target affective, behavioral, and cognitive components.

Conceptualization models

- three-systems ABC conceptualization

- Functional Analysis ABC

- Activation Beliefs Consequences

- Basic longitudinal conceptualization

- The cognitive hierarchy and levels of conceptualization

Transactional model of stress Beck’s original cognitive model of anxiety

- Anxiety mode and dual belief system

- Schemas of threat and vulnerability Beck’s revised cognitive model of anxiety

- Immediate fear response

- Automatic thoughts and images

- Automatic physiological responses

- Automatic behavioral responses

- Strategic processing and secondary appraisal

- Strategic behavioral coping (avoidance & safety seeking)

- Worry and thought control

- Reappraisal of threat and coping

Collaborative conceptualization

- Cognitive conceptualization of anxiety (worksheet)